|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy |

The Judiciary Power of Discretion in Sanctioning the Facilitation of Unauthorised Stay in Poland

Witold Klaus and Monika Szulecka

Institute of Law Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poland

|

Abstract

Migration control in Poland is significantly based on internal control

practices carried out by street-level bureaucrats representing

both law

enforcement agents and low-level judges equipped with discretionary power. Based

on empirical data from 243 criminal cases

of facilitating unauthorised stay in

Poland, we reflected on how the mentioned actors and, in particular, criminal

judges interpret

the existing provisions and to what extent they study cases

independently or simply follow the logic of the law enforcement. We based

our

analysis on two distinct forms of identified cases of ‘supporting’

irregular migration; that is, participation in

sham marriages and involvement in

document fraud. We conclude that judges lacking expertise in the field

relatively new to them may

be less prone to question the effects of the

preparatory proceedings, and they are not keen to look for any answers for

themselves,

especially to scrutinise and refer to the European Union law or

jurisprudence. In their ‘craftwork’, they face cases

that seem

similar to them and, thus, not deserving of special attention. Judges lack the

broader knowledge and possibly also reflexive

thinking in assessing

migration-related criminal cases brought to the courts by border guards, who

prove their effectiveness inter

alia through numbers of detected facilitators,

not necessarily the roles played by them. All this may lead to unnecessarily

broadening

the scope of control over immigrants and a failure in achieving the

objectives of criminal provisions.

Keywords

Facilitation of unauthorised stay; criminal sanction; judiciary discretion;

Poland; illegalisation of immigrants.

|

Please cite this article as:

Klaus W and Szulecka M (2021) The judiciary power of discretion in sanctioning the facilitation of unauthorised stay in Poland. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy. 10(3): 72-86. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.2042

Except where otherwise noted, content in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence. As an open access journal, articles are free to use with proper attribution.

ISSN: 2202-8005

Recent years have witnessed a change in the migration status of Poland. It remains a country of emigration, but more and more often, it is also being chosen by immigrants as a destination in Europe, which confirms Poland’s status as a member of the Global North (see Castles 2004). In the relatively short history of foreigners’ arrivals to contemporary Poland (which started after 1989), it has only been in the second decade of the twenty-first century that migration itself and migration policy have become widely discussed and politicised issues. To some extent, these processes accompanied the increasing number of immigrants spreading over the territory of Poland and on its labour market in particular. The latter partially stems from regulations less restrictive than in other European Union (EU) countries, offering more attractive economic conditions. Taking arrivals of non-nationals to the fore of public and political debate has also been the result of the post-2015 political crisis in the EU, caused, among other things, by the sharp increase in numbers of asylum seekers reaching the southern borders of the EU and their journey to other member states, especially Germany and Sweden.

All the factors mentioned contributed to a rather restrictive state approach towards immigrants, other than the demanded economic ones. Asylum seekers, especially Muslims, have already been facing rejection at the border. Poland also refused to relocate refugees within the EU relocation scheme. Harshening the stance on immigration has been justified by the need to prevent uncontrolled migration, social tensions and threats to security (see, e.g., Klaus 2017). However, at the same time, migratory phenomena in Poland have been predominated by arrivals of economic migrants, especially from neighbouring Ukraine (Klaus 2020). The latter enjoyed rather welcoming legal conditions followed by favourable administrative practices. Although an uncontrolled inflow of migrants across the EU external border to Poland has never constituted a serious challenge, the fear of being affected by ‘unwanted’ immigrants (i.e., asylum seekers or irregular migrants) has become the main driver of migration control and policy in Poland. To a significant extent, such an approach has been built upon imaginary, ‘second-hand’ experiences, usually filtered by media or unsupported predictions more than upon real phenomena.

In this article, we reflect on one of the aspects of migration control in Poland, namely, the prevention of facilitating unauthorised residence on the Polish territory. Based on the empirical study involving court files related to this offence, we analyse the role and consequences of discretion in judicial decisions sanctioning behaviours identified as for-profit support of foreigners’ stay in Poland in breach of the law. The points of departure for further analysis are theoretical thoughts regarding discretion in the judicial practice, especially in the area of migration control, that directly corresponds to the topic of our empirical study.

Immigration-Related Control Priorities Declared by the Polish Authorities

Since December 2007, Poland has been a part of the Schengen zone, without regular controls at the borders with other EU countries. In 2020, there were 4,156 apprehensions for unauthorised border crossing (including attempted), and only 2,361 of those apprehensions concerned the external border (in 2019, the respective numbers accounted for 5,188 and 2,164) (KGSG n.d.). The greater focus on detecting or preventing unauthorised border crossings of internal borders (especially with Germany) has been visible in the official statistics since 2014. Only a small fraction of the identified unauthorised crossings of the external border relate to the ‘green border’ (251 cases in 2020 and 200 in 2019), and usually, they take place at the border with Ukraine. The majority of unauthorised crossings of the external border, often with the use of fraudulent documents, were identified within the border crossing points (KGSG n.d.).

Despite a rising trend in the number of detected unauthorised border crossings between 2011 and 2018 (with a peak in 2016), these numbers are extremely low compared to the registered scale of cross-border mobility, exceeding 35 million foreigners crossing the external border each year. The same could be also said about the criminality perpetrated by foreigners in Poland. Not only are the numbers relatively low (constituting about 1% of the total number of registered crimes committed in Poland), but their severity is not alarming, as more than 80% consist of three types of offences: driving a vehicle while intoxicated, theft or other property-related crimes and document fraud (usually connected with the process of authorisation of entrance or stay in Poland) (Rzeplińska and Włodarczyk-Madejska 2018).

Why does mobility through the Polish borders raise so many concerns, even if the scale of the identified unauthorised cross-border movement remains insignificant? In the early 1990s, Poland was chosen by migrants transiting from the East to the West. This mobility was often seen as undocumented and supported by smuggling networks that were insufficiently tackled (or sometimes tacitly tolerated) by control institutions in both exit and entry directions (Jandl 2007; Okólski 2000). However, clandestine entries were not associated with long-term unauthorised stays due to the transit or shuttle character of cross-border mobility. Also, the relatively liberal legal regime of entering Poland enjoyed by most frequent visitors from the neighbouring eastern countries did not contribute to the presence of irregular migrants on Polish territory. Nevertheless, in the context of restricted access to the 15 ‘old’ EU countries and the observed migratory pressure, irregular migration across Polish territory had remained a phenomenon to be urgently dealt with in a country that had aspired to become an EU member state and to take advantage of the freedom of movement within the EU borders. As required by the EU, Polish authorities had to specify laws and build an institutional system to prevent irregular migration on EU territory (see, e.g., Vermeersch 2005).

The post-accession developments in Poland’s immigration laws led to an increased scope of legal paths for entering both the territory and the labour market in Poland. At least in theory, this should serve for prevention of unauthorised entries and decreasing of the demand on facilitators’ services. However, the widened scope of legal channels of immigration was not accessible for all third country nationals and was not accompanied by liberal laws or effective procedures allowing for easy legalisation of further stay. This, in turn, meant the risk of illegalisation of migrants’ stays (Bauder 2014) and, consecutively, the development of strategies to get out of ‘irregularity’. Thus, relatively easy access to legal entry for certain categories of migrants (especially migrant workers), together with the restricted access to long-term stay or international protection, resulted in a marginal scale of ‘illegal’ migration and predominance of ‘semi-legal’ forms of migration and migrant adaptation. This is how the phenomenon of irregular migration is perceived and described by the representatives of the migration control apparatus in Poland (Szulecka 2016a). ‘Semi-legality’ or ‘semi-compliance’ refers inter alia to situations when valid documents authorising a stay are accompanied by activities identified as contradictory to purposes of the documents issued for migrants (see Kubal 2013; Ruhs and Anderson 2006). In the Polish case, this term can be applied to migrants with visas authorising them to work or study and who undertake other activities upon arrival to Poland. They work instead of studying or run their own business instead of being hired by the employer mentioned in the visa application process. The term is also applicable to migrants who ‘work for papers’, for example, when they sign disadvantageous work contracts just to be ‘registered’ and to have a chance for further legalisation. At the same time, their income-bringing activities are, in fact, performed in an undeclared mode (Szulecka 2016a).

Considering the above remarks, migration policies targeting irregular migration in the Polish context are more about those ‘illegalised’ and ‘overstayers’ than those ‘undocumented’. It is also more about ‘semi-compliance’ rather than full non-compliance, translating into illegal entry followed by unauthorised stay (Szulecka 2016a). Thus, migration control is not reduced to strict border control (within and outside border crossing points). It is significantly based on internal control practices involving more actors: border service, labour inspectorate and offices responsible for issuing work or residence permits. These street-level bureaucrats (Lipsky 2010) are equipped with discretionary power and sometimes imperfect guidelines on law implementation. The latter may result from the legislation and institutional system becoming less transparent and more complex. This, in turn, may be linked to the fact that migration control has become multiscalar, based on regulations of low quality from the legislative point of view being blurred and leaving room for different interpretations, followed by guidelines released under political pressure.

Thus, the street-level bureaucrats decide whom they control and how and whose behaviours may be eventually assessed by the courts. There is an extensive body of literature presenting discretion in the everyday approach of law enforcement agents towards immigrants or people the agents view as immigrants (Brouwer, van der Woude and van der Leun 2018; Dekkers, van der Woude and Koulish 2019; Macías-Rojas 2016; van der Woude and van der Leun 2017). In this paper, we would like to demonstrate the discretion in sentencing from criminal judges. We refer to rulings in cases of facilitating the unauthorised stay of immigrants in Poland issued by criminal courts. The latter deal with cases of unauthorised border crossing or the facilitation of irregular migration since they are specified as crimes in the Polish context.

Bearing in mind the scientific dispute as to whether judges should be studied within the street-level, bureaucracy theoretical framework (see, e.g., Biland and Steinmetz 2017), we claim that those who process criminal cases at the low-level courts suit the mentioned framework. Although street-level bureaucrats have been recently associated with public administration and the government (Camillo 2017), according to the original ‘list’ of the examples of this category of actors proposed by Michael Lipsky (2010: 3), lower courts judges have also been included in it. Despite independence inscribed in their profession, to some extent, they act as frontline agents, although their contact with involuntary clients (including defendants) involves greater distance than in the case of other street-level bureaucrats. Moreover, such contact is often intermediated by other actors such as lawyers or court employees (see also Biland and Steinmetz 2017: 23). Criminal judges assess behaviours of people identified by other street-level bureaucrats as offenders, which means that their decision-making process vastly depends on the discretionary power of those who are more at the front line. In a number of cases, they accept (they ‘rubber stamp’) the decisions made by law enforcement agents. Even though they should independently assess those cases based on their own knowledge and using the wide range of tools available to them, it is easier to base decisions on someone else’s assessment (Lipsky 2010: 128–131).

The Role of Discretion in the Criminal Justice System

Discretion is a pivotal idea built within the criminal justice system in liberal democratic countries (Tillyer and Hartley 2010). Without it, the whole system would not function effectively and efficiently and would bring much injustice. In general terms, discretion is used to mitigate situations when the law or a certain legal regulation departs from the reality of everyday lives because it simply cannot follow its constant liquidity. Therefore, the role of the judges’ discretion is to prevent the law from being unjust (Dworkin 1977; Thomas 2003). Discretion in the criminal justice system could be seen on at least three levels and is implemented by three different types of actors. The first type encompasses police officers who decide which person should be stopped or arrested. The second type includes prosecutors who decide which cases should be further prosecuted and eventually brought to the court. The third type relates to judges who not only decide on conviction but also on the severity of the punishment (Bushway and Forst 2013; Tillyer and Hartley 2010; van der Woude and van der Leun 2017).

Besides the discretion on a ‘street-level’ described above, the fourth type of actor with discretionary power has been exposed by Shawn D. Bushway and Brian Forst. They relate it to the political level (called ‘Type B discretion’) and argue that the creation of criminal justice policy and legislation by politicians is also strongly discretionary. Politicians’ roles are to set certain rules and boundaries for judges (and other actors of criminal justice systems) to limit them in their process of sentencing (e.g., policing or prosecuting). This type of discretion is used to impose limits on the original discretion that judges were equipped with (called by the authors, ‘Type A discretion’) (Bushway and Forst 2013). This process is not new because discretion has always had its limits. As Ronald Dworkin wrote, ‘discretion, like a hole in a doughnut, does not exist except as an area left open by a surrounding belt of restriction’ (Dworkin 1977: 31). The scope of this ‘hole’ nonetheless differed in time and space. In recent years, it is quite broad, despite the fact that politicians always have the temptation to limit it. However, it usually brings detrimental effects, even if, in the beginning, politicians had good intentions to correct adverse practices in sentencing (Reyes 2012; Thomas 2003).

Discretion also has its dark side. It enables the treatment of people differently in the same situation and allows for discrimination against them. There is an extensive body of literature on racial discrepancies in sentencing in a number of Global North countries (Bushway and Forst 2013; Tillyer and Hartley 2010). Significantly less academic attention, though, was put on researching interconnections between sentencing and the immigration backgrounds of defendants (Aliverti 2013; Macías-Rojas 2016; Reyes 2012; Sklansky 2012), especially if it was not related to migration law (and migration crimes) and did not lead to deportation or detention of immigrants (with the exception: Brandon and O’Connell 2018). There is no doubt that judges, being a part of the society, are not resistant to the common perceptions of some groups and widespread urban legends of alleged dangerousness of other groups (like immigrants) embedded into the social tissue. Since even police officers share stories of the criminality of representatives of certain nationalities that are not proven and not based on their own experience (Brouwer, van der Woude and van der Leun 2018), representatives of other professions closely connected to and working with law enforcement agents most probably share those beliefs as well. Sentencing as a process is very individual in the sense that it is largely based on penal philosophies and the general attitudes of a judge (Tata 2007: 433–434).

Conversely, though, sentencing is also a social process that:

is not overwhelmingly focused on the judge as the decision maker, but rather as part of a sequence in a decision process, where the judge is a member (albeit the most central) of a collaborative sentencing world. (Tata 2007: 442)

In this sense, the judge takes into account the satisfaction of ‘clientele’ of the criminal justice system, which includes all actors involved in the case (starting with law enforcement agents and ending with defendants) and stretches out to the society (Tata 2007: 439–441). By no means does this dismantle the idea of independence of the judiciary. However, the presence (or absence) of different actors and the roles they play before and during the trial leaves an imprint on each judicial decision. The influence on the process of sentencing becomes clearer if we think of this process as a pragmatic enterprise and a judge as a craftsman who perceives their work as quite boring and repeatable (Tata 2007: 427–428) and who is a part of a broader societal organisation.

Taking a closer look at the criminal justice system and its actors through those lenses allows us to see the processes of co-independency of different actors and discretion leaking throughout the system. Police or border guard officers, or ‘rule enforcers’ (Becker 1966), try to prove their existence and effectiveness as protectors of the society from danger (in this case, unwanted immigrants). To do so, they use available legislation, and they are ‘being creative’ (van der Woude and van der Leun 2017: 39) in the process of ‘broadening’ its scope when needed. To be effective, they should present a well-designed case (from evidential and legal points of view) to a prosecutor who could file it to the court without additional work (Szulecka 2017). This way, both institutions show their efficiency. It is also easier for the judge to follow the logic of the case brought by the prosecutor (and previously by the border guard officers) than to create a different and cohesive new one.

That is why, in most of the cases (e.g., in Poland between 2013 and 2018 in more than 97% of the criminal cases), judges declare the defendant guilty and impose different forms of punishment (MoJ 2019: 122). This trend is even more clear in cases (discussed below) when immigrants are involved, especially if they are not present during the court’s hearing since they are no longer in Poland. According to Polish law, it is possible that that the verdict is released without the presence of both the defendant and their lawyer. Additionally, Polish legislation envisages the institution of conviction without a trial (Article 335 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, the Act of 6 June 1997), which depends upon an agreement on the scope of liability and the punishment, achieved between the prosecutor and the defendant in the preparatory phase. It is applicable to circumstances not raising further doubts and, thus, not requiring evidentiary processes before the court. Judges serve only to confirm the guilt and issue a verdict already agreed by all the parties. Therefore, following the prosecutors’ demands may be the optimal ‘strategy’ for a judge since it allows for avoiding additional work and long court proceedings. The judges see, in such institutions as conviction without the trial (plea bargaining), a potential for making the system of justice more effective and operating faster (Królikowska 2020: 248–252).

Another aspect of the judiciary craftwork in cases involving new and rarely encountered types of crime (like facilitating the unauthorised stay of a foreigner) is the lack of expertise of judges in similar cases. Moreover, judges encounter the challenge of the very limited and quite weak legal literature about that crime, which is not easily available to them; in Poland, judges rely mostly on two legal e-platforms containing legal acts with practical commentaries. The abovementioned two issues again create a space for replication in the sentence of the logic and rationale presented by the prosecutor in an indictment rather than to elaborate a new narration by the judge themself. Those practices could go far beyond the discretion, though, and may bring into the sentencing misinterpretation of the provisions and broadening the scope of criminal liability despite lack of a legal basis to do so.

Aim, Scope and Methods of the Analysis

The experience in the legal assessment of the facilitation of unauthorised stay of migrants is relatively short in the Polish context. The criminalisation of for-profit aid in the unauthorised stay of foreigners in Poland is directly linked with the harmonisation of the Polish regulations with EU law. In 2004, the relevant provision was introduced in the Polish Criminal Code (Article 264a of the Polish Criminal Code, the Act of 6 June 1997, hereinafter the PCC) as part of the necessary transposition of the ‘Facilitators’ Package’, that is, the Council Directive 2002/90/EC defining the facilitation of unauthorised entry, transit and residence and the Council Framework Decision 2002/946/JHA on the strengthening of the penal framework to prevent the mentioned offences. The directive includes a very vague description of the subject of criminalisation: ‘assistance in residence within the territory of a Member State in breach of the laws concerning the residence of foreigners’. This definition, accompanied by provisions of the framework decision, allowed member states to punish various behaviours, including those that indeed aim to support migrants in undocumented stays and those that aid the legalisation of their residence status involving unlawful measures, for example, by facilitating marriages of convenience.

The Polish legislator expanded on the minimum requirements demanded by EU law (intent to gain financial profit) and introduced penal liability for acts facilitating unauthorised residence if the perpetrator takes action for personal profit. According to Polish law, in exceptional cases, when the offender has not received financial profit, extraordinary mitigation of punishment or even decree is applicable. Offenders with unmet expectations of personal profits are still subject to punishment, and, at least due to this difference in consequences of determining the gain as material or personal, it is important to specify what in fact meets the criteria of personal profit. However, due to the scarce case law in this respect and very poor legal doctrine, which hasn’t been developed on this matter, this task is challenging to a judge. Therefore, determining this became one of the objectives of our empirical study, the first so extensive research into this issue in the Polish context.

The study of convictions for enabling or facilitating the unauthorised stay of migrants was conducted between 2018 and 2020. According to data from the National Criminal Register (the central database including information about all persons convicted in Poland, held by the Minister of Justice), between 2004 and 2017, in 287 criminal cases, at least one person was convicted under Article 264a of the PCC. Based on this information, we decided to apply an exhaustive sample and include all cases in our analysis. Therefore, having obtained reference numbers of all relevant cases, we sent requests to obtain access to the files from all 112 courts where verdicts, including conviction under Article 264a, were issued. Nineteen per cent of the preliminary sample was unavailable for research purposes. The reasons behind this were usually the ongoing court proceedings (e.g., appeal procedure) involving ‘facilitators’, the use of the files by other courts than those that concluded the case in the first instance and, in rare cases, denial for accessing the files. Therefore, the final sample included 243 cases meeting the criteria issued by 102 courts in different regions of Poland. In all these 243 cases there were altogether 499 persons convicted of facilitation of the unauthorised stay of a migrant.

Regarding the methods of analysis, we studied all materials available in the files (all information at the judges’ disposal) and verdicts with their reasonings. The analysis of the files was conducted between April 2018 and February 2019, and it was mostly based on the use of a complex, multivariant questionnaire aimed at collecting all the necessary information about the facilitators, recipients (i.e., migrants whose unauthorised stay was facilitated), the form of the offence and profits gained or intended. Some of the questions were open-ended, which allowed the gathering of information about all the cases to be later analysed in a qualitative manner. Usually, these data concerned the motives of the modus operandi of the offenders as well as the character of the relationships between the facilitators and recipients.

Regarding the fact that the sample had exhaustive character, we can conclude that the number of cases conducted by each court was not high. Almost half of the courts (50 out of 102) that had experiences in convictions based on Article 264a of the PCC adjudicated only one such a case between 2004 and 2017. Five or more cases concerning this crime were carried out by only 12 courts (out of 102 included in the sample). These observations, along with the unavailability of almost 19% of cases from the preliminary sample, means that drawing conclusions on the shares of specific forms of the offence and the specialisation of courts should be done cautiously. Nevertheless, the scope of the study, including an in-depth analysis of all files concerning each case, allows for discussing which behaviours and circumstances the law enforcement and judges found deserving of criminal sanctions with regard to the studied provision.

Understanding of Facilitation of Unauthorised Stay by Law Enforcement Agents and Judges

Among the studied cases, the ones involving document fraud prevailed (constituting 37% of the sample). In turn, involvement in a marriage of convenience (in different roles) was the subject of 20.2% of the studied verdicts. Other distinctive forms identified in the study included assistance in illegal border crossing (12.8%) and hiring an irregular migrant combined with providing them with accommodation (12.2%). Despite the limitations of the sample, it is possible to observe a kind of specialisation in some courts, which leads to the question about the abovementioned tendency to follow the path already known. For instance, 11 out of 14 cases conducted by one of the district courts in Łódź (located in central Poland) concerned false declarations of paternity. Interestingly, there were altogether 20 cases of the offence in the entire sample (243 cases), and more than half of them were adjudicated by one court. In turn, 12 out of 15 relevant cases adjudicated by judges from the Regional Court in Lublin (in eastern Poland covering the border area neighbouring Ukraine) assumed assistance in an illegal border crossing. However, the latter case raises questions about both the legal basis of conviction and the form of the offence. The courts had at their disposal other provisions to sanction assistance in an illegal border crossing. However, they decided to use Article 264a of the PCC in imposing sanctions on those who provided migrants trespassing Poland in an irregular manner with short-term accommodation (for a night or two). Most probably, this kind of action—providing shelter or accommodation even for few hours—led judges to interpret the behaviour of the driver or guide assisting in irregular border crossing as a form of facilitating the unauthorised stay of the migrants. However, the offenders’ clear intent related to the facilitation of travel in and out of Poland, not staying in its territory. In other words, both the intention and action did not fit the description of the crime stipulated in Article 264a of the PCC.

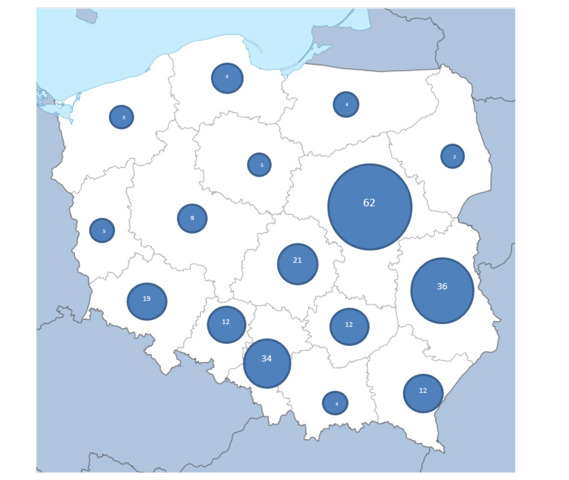

The understanding of facilitation of unauthorised stay is significantly diversified among regions. The geographical distribution of the cases (see Figure 1) indicates a considerable degree of diversification of the number of cases conducted in different regions of Poland. To some extent, it may be justified by large numbers of immigrants residing in certain areas of Poland (in particular, in the central part, including the capital city of Warsaw) or proximity to the external border. However, these arguments do not explain such big differences, for example, along the eastern border, or the insignificant representation on this map of larger cities in Poland in which migrants reside.

Figure 1. Geographical distribution of the studied cases throughout Poland (by regions)

Source: This figure is adapted from the map available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Poland_location_map_white.svg#file licenced under CC BY-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Visible discrepancies in judicial decisions among different regions have been observed in the research focused on criminal cases for many years now. However, they refer mostly to the disparities in sentencing penalties for particular crimes (Gruszczyńska, Marczewski and Ostaszewski 2014). In the cases studied, the discrepancies should rather be explained by other factors. These include, for instance, the specialisation of the rule enforcers (Becker 1966), who are, in this case, border guards on a local level, as well as their ‘creativity’ (van der Woude and van der Leun 2017: 39); the prosecutors’ approach to offences investigated by the border guards; and specific kinds of the abovementioned ‘craftwork’ observed among Polish judges (see also Tata 2007).

The primary analyses of the abovementioned data, supported by outcomes of another study involving border guards (see Szulecka 2016b), allowed for identifying a few areas in which the question about the role and consequences of the discretionary power was crucial. It refers to perceptions and assessments by law enforcement and courts with regard to two specific forms of ‘supporting’ irregular migration, that is, participation in marriages of convenience and involvement in document fraud. There is no doubt that the mentioned behaviours constitute breaches of the law. However, a more in-depth analysis of these cases raises concerns about whether the existing provisions are applied appropriately and whether both law enforcement and the courts’ activities are based on facts or unsubstantial presumptions.

The (Un)Obvious Connection between Offences against the Credibility of Documents and Irregular Migration

According to empirical data, the use of provisions related to offences against the credibility of documents in criminal cases identified as the facilitation of unauthorised stay of migrants did not reflect any regularity. In general, in 44% of the studied cases, the courts considered the offence of facilitation of unauthorised stay as a form of document fraud. However, there was no consequence in legal qualification of similar actions. For instance, in 3.7% of the analysed cases, document fraud accompanied the false declaration of paternity. For another court, the same action, namely, false declaration of paternity, was assessed as a form of the facilitation of unauthorised stay without referring to provisions concerning document fraud (which applies to 4.5% of the studied cases). Since document fraud seems an inevitable element of the false declaration of paternity, it could be interesting to pay more attention to factors influencing law enforcement or judges in qualifying similar deeds as either document fraud solely or the facilitation of unauthorised stay through document fraud. To some extent, this question may be linked to the issue of quality of provisions and understanding of these provisions among legal professionals. However, this would require additional study with a different methodology applied.

Many of the identified document fraud cases treated as a form of facilitating unauthorised stay were linked to the use of documents submitted in the process of visa applications, including work offers for foreigners. These documents, commonly called ‘declarations’, are linked to an administrative instrument of controlling foreigners’ access to the labour market in Poland for temporary purposes (Vankova 2020: 111–114). It is applicable to migrants from non-EU countries participating in the Eastern Partnership program, and declarations can be used in the visa application process as supporting documents. Fifteen per cent of persons convicted for the facilitation of unauthorised stay were punished for declaring the false intent to hire a foreigner or being involved in ‘trading’ in such declarations. Importantly, the administrative provisions on declarations did not address the situation of changed intents or unforeseeable circumstances, eventually leading to giving up the job offer (by both the migrant and potential employer). When judgments were passed, there was also no legal basis for the refusal of registering such a declaration by a local labour office. Thus, the verification of intentions of potential employers was not obligatory, and the possible detection of ‘fake’ employers (unable or unwilling to hire anyone) did not lead to any consequences (not to mention how, in practice, it is difficult to unveil the ‘untrue’ intentions). Such suspicion could be, at most, reported to the border guard, whose control activities were perceived as the most effective way of discouraging people from using this instrument for purposes other than hiring foreigners.

The scarce regulation of registering declarations and the revealed cases of trading in them among migrants interested in getting visas to enter Poland led the law enforcement to identify this administrative procedure as one of the channels used by (would-be) irregular migrants and facilitators. According to both the courts and the border guards, declarations submitted by ‘fake’ employers (unwilling or unable to employ workers) served migrants (for whom declarations were submitted) only to obtain visas and work in an undeclared fashion further on—in Poland or other EU countries (Szulecka 2016a). Ukrainian migrants possessing Polish visas and working in other EU countries became a phenomenon known to migration control services in other EU countries, including Czechia, Lithuania and Germany. The scale of the presence of Ukrainian workers with Polish visas in the Czech labour market led to recommendations posed by non-governmental bodies to recognise their semi-legal status and recognise this phenomenon as a risk for worker exploitation (Trčka et al. 2018: 51).

For an analysis of the role of judicial discretion, it is necessary to step back to the phase when the law enforcement agents faced the dilemma of if and how they should react if they supposed that employers appearing at the local labour offices, declaring intent to hire particular foreigners, were involved in the facilitation of irregular migration. The answer to this question is connected to the abovementioned scarce, incomplete regulation of the procedure based on a declaration. Additionally, in the statement issued by the Polish Attorney General, it was advised not to qualify the obtainment of a visa based on a declaration (a signed document in paper or in electronic version) as a form of an offence against the credibility of documents. However, until this statement was released, the latter legal qualification was seen as the most proper one. One of the border guards commented on the challenges in investigating the cases when declarations of intent to hire foreigners were used for other purposes:

The Attorney General’s office in Warsaw issued a legal opinion that, to some extent, changed the way prosecutors proceeded in cases of declarations. Of course, ... now it is more difficult to prosecute. Earlier, it was qualified as obtaining attestation of an untruth, obtaining a visa under false pretences, and this meant that someone [a foreigner] immediately acted with an intent not to work for the particular employer and to use a visa to enter the country, but not to start working ... But at one moment, ... [in 2013] it was decided that this qualification is improper ... And the prosecutors accepted this because it was the opinion of the Attorney General’s office. However, if we manage to gather proof of other offences, typical for border offences, such as ... illegal border crossing or for-profit facilitation of illegal stay [of foreigners] ... then the prosecution is undertaken. But it is more difficult than in the case of attestation of an untruth and obtaining a visa fraudulently. (Officer of the local Border Guard outpost)

The above quote explains why deeds indirectly leading to visa obtainment, which could be prosecuted with provisions related to the credibility of documents, became identified as a form of facilitating the unauthorised stay of migrants. However (and surprisingly enough), not all prosecutors or border guards followed these guidelines since they questioned their binding character. The courts revealed varied approaches to construing the employers’ declarations. For some judges, the cases brought to the courts as the facilitation of unauthorised stay combined with document fraud meant only the support offered to migrants unlawfully staying in Poland. In one of the reasonings to the appealed verdict convicting the potential employer of enabling unauthorised stay, the court stated that declaring the intent to hire a foreigner cannot be treated as a part of the offence against the credibility of documents: ‘Attestation of an untruth by a public officer means confirming facts that did not happen, or modifying the actual fact or withholding these facts’ (case no. 135). Since employers submitted their declarations about the future, by nature, it could not be identified as a form of document fraud. However, in other cases, judges, without deeper reflection, confirmed charges proposed by prosecutors or border guards, that is, false declarations identified as document fraud used to facilitate the unauthorised stay of migrants.

The analysed cases of the facilitation of unauthorised stay also encourage a look at the judges’ discretion in assessing the motives of persons convicted for this offence. As it was already mentioned, the Polish legislation enables sanctioning offenders who gain both material and personal profit. In some cases, Polish citizens, expecting a financial reward, decided to declare the paternity of a child born to a foreigner staying in Poland without valid documents. This led (or could lead) to authorisation for the stay of the mother and child. However, there are more doubts in the cases of persons whose gains were less obvious or sometimes not even determined by the court but classified as financial.

It also happened that profits of a similar kind (e.g., sweets, cigarettes or alcohol) were perceived as personal profit (possibility to obtain such goods for free), whereas other judges noticed the material character of them. Importantly, the value of such profits was usually not determined by the courts. Such statements concerning profits could be found in the rulings that concerned persons in unfavourable economic situations, encouraged or somehow forced by the main organisers to present declarations of intent to employ foreigners to local labour offices. Moreover, such ‘facilitators’ were easy targets for law enforcement, contrary to the main organisers, whose identity usually remained unrevealed. Targeting actors involved in this scheme at the lowest level shows, in fact, the failure of law enforcement in the real prevention of this phenomenon. They could prove their effectiveness in statistical terms, whereas, in fact, their effect on reality was rather insignificant, and often judges did not change this direction. Our study has proven that some judges followed the logic of the border guards and did not question both the legal qualifications and objectives of punishment in such cases.

Punishment for Facilitating Marriages of Convenience

The countries of the Global North have largely sealed off legal migration routes for individuals from the Global South. As a result, a marriage with a citizen or a permanent resident of the Global North has become one of the few remaining ways for undocumented persons to obtain the right of entry there or to legalise their residence (Beck‐Gernsheim 2007), leading to a proliferation of so-called sentimental fraud; grey, bogus or sham marriages; or marriages of convenience (D’Aoust 2013: 104). This, in turn, results in increased efforts to detect such practices, prosecute them and punish the perpetrators, which means increased suspicion on the part of law enforcement with regard to marriages with foreigners from the Global South; the scrutiny of such unions; and, in many countries, even the introduction of restrictions on legalising the residence of migrant spouses (D’Aoust 2013). Convictions based on the involvement of a person in the organisation of a sham marriage are based on the identification that a particular marriage fulfils that definition. The space for judicial discretion is wide open here, as the definition of such marriages is particularly vague (Rude-Antoine 2005), and practical application in real situations is very difficult (especially when none of the spouses cooperates with the law enforcement) and potentially leads to false conclusions.

In our research, in 23.5% of cases, there was a conviction for the facilitation of sham marriages. This concerned 145 (29%) of the 499 offenders included in the study. Though, it is debatable whether the current provision (Article 264a of the PCC) should be used so broadly. In the judicial practice of Polish judges, a marriage of convenience happens to be linked with other crimes, for example, document fraud, using deception to obtain attestation of false information from a public official and giving false evidence during an administrative procedure legalising the foreigners’ residence. It seems that there is no common thread linking all the rulings. In the studied cases, 3.3% related to marriages of convenience, qualified as a form of facilitating unauthorised stay and, at the same time, another type of offence, for example, document fraud.

In fact, the legislation in matters pertaining to sham marriages gives rise to many more questions, such as who should be punished. In some cases, it was the foreigner who had gotten married, having committed the crime of ‘self-facilitation’ of residence in violation of existing laws, even though the law clearly states that the facilitation of unauthorised residence should only be applied to another person, not the immigrant themself. Such court rulings are evidently contra legem and binding interpretations of EU law (see, e.g., Opinion of Advocate General Bot in Case C‑218/15 [point 28]; InfoCuria 2016), assuming, among other things, that the ‘Facilitators’ Package’ was aimed at punishing smugglers and facilitators, not irregular migrants. Nevertheless, 10% of convicted facilitators covered by our study were the same persons whose stay was facilitated. In legal terms, their behaviour was qualified as assistance or instigation. However, this does not change the fact that they were punished for facilitating their own stay.

As far as sanctions for sham marriages are concerned, there were cases when the punishment raised serious concerns. In several disputes (concerning 20 offenders in total), the sentenced individuals were just legal witnesses at a wedding. The court argued that their mere presence during the wedding in that capacity warranted punishment since they should have realised the circumstances of the wedding were ‘suspicious’ and might be used as a pretext to legalise the stay of the migrant spouse. The witnesses’ ‘conspiracies’ to facilitate unauthorised residence were explained as follows: had they refused to appear as witnesses, the marriage would not have taken place, since, according to Polish law, a couple can only be married in the presence of two witnesses who are over 18 years old (case no. 174). The cause-and-effect relationship between the events in the argument is so contrived that the thought process behind the decision is nothing short of preposterous. One wonders whether it is a case of pre-emptive justice when an entirely legal behaviour (like entering into marriage, which does not become legally null and void just because it is arbitrary) is penalised. Moreover, its correlation with the future and prospective illegal conduct (i.e., using the marriage to legalise one’s stay) is not obvious and would in any way be a distant perspective. This would also require another person to undertake a series of actions that the punished individual is unable to predict or prevent. As it is, it seems that it is possible to punish lawful assistance in a pre-crime situation of sorts. In other words, the practice justifies ‘abandoning the long established requirement of criminal law that attempts must entail acts “more than merely preparatory” to a crime’ (Zedner 2007: 192).

In another case (case no. 34), a father was sentenced for arranging his son’s marriage to a Polish woman, having promised her 250 EUR for the wedding (held in Ukraine) and another 250 EUR for the divorce (in the end, the Polish wife never received the money). Upon their return to Poland, the couple moved in together and had a child. During the trial, they still lived under one roof, and even the court admitted that there was no basis for assuming that the relationship was a sham. And yet, the court sentenced both the father, who had arranged the marriage, and the Polish wife of the foreigner. The basis for the conviction was the original intent of using the marriage to circumvent the immigration law. In general, the legal provision requires that the perpetrator obtains material or personal profit as a result of the crime (or has the intent to obtain such). Since the parent paid the Pole to participate in the marriage, they naturally did not profit from their actions in the financial sense. Therefore, the courts opined that the profits were personal, as his child secured the right to reside in Poland and stay close to the parent. This raises serious doubts as to whether punishing individuals for obtaining personal gains does not excessively expand the scope of criminality and interfere too much in the private lives of individuals.

Still a Discretionary Power or an Abuse of Power by the Judges?

The abovementioned research affords thought-provoking conclusions with respect to judges and their role in safeguarding individuals’ rights in situations when authorities wish to expand control beyond the limits established by the law. For the most part, courts are depicted as guarantors upholding human rights, which is often exemplified by the activity of international courts (Hamlin and Mellinger 2018). However, the role of national courts cannot be overestimated either (Perry 2003). In the literature, it has already been established that migrants have limited access to judicial protection and experience lower standards of legal protection during court proceedings (Dauvergne 2013) as well as harsher treatment in criminal proceedings (Brandon and O’Connell 2018; Macías-Rojas 2016).

Research has demonstrated that Polish courts broaden the extent of the criminalisation of migration-related behaviours, even beyond the limits of criminal law provisions, far beyond legally permissible discretion. It is difficult to be certain whether it is driven by nationalist sentiments rife in Polish society and the peculiar de-Europeanisation of common values (Klaus 2020). It might have taken its toll on judges, causing their anti-migrant attitudes. Or perhaps it is a manifestation of professional routine and following the clientele’s expectations—rubber-stamping the materials provided by the prosecutor in the indictment (Lipsky 2010: 129–130) without having to pore over regulations to fully understand them (Tata 2007).

The process described above shows that justice and punishment in cases related to immigrants are applied preventively (Ashworth and Zedner 2014) or even pre-emptively (Guittet and Brion 2017; Mantello 2016). Therefore, they have an important social function, since, as Michel Foucault notes:

Punishment in general, is not intended to eliminate offences, but rather to distinguish them, to distribute them, to use them ... Penality would then appear to be a way of handling illegalities, of laying down the limits of tolerance, of giving free rein to some, of putting pressure on others, of excluding a particular section, of making another useful, of neutralizing certain individuals and of profiting from others. In short, penality does not simply ‘check’ illegalities; it ‘differentiates’ them, it provides them with a general ‘economy’. (Foucault 1977: 272)

Migrants and a fear of migrants cumulated in the shape of a number of laws punishing various migratory behaviours (Macías-Rojas 2016; Stumpf 2006). This is a form of political discretion (Bushway and Forst 2013), and it is followed by discretionary power imposed by representatives of the criminal justice system on every level. They exercise it ‘creatively’ within the law (van der Woude and van der Leun 2017: 39)—as reflected in the words of one member of the authorities, ‘you can tailor your response to a particular case and you have a great range of deterrent ... It just helps us to do the job’ (Aliverti 2012: 422). When the legal provisions seem to be too narrow, discretion can broaden alongside the scopes of the law. But then the question should be raised: is it still a discretion, or is it a completely new phenomenon directed against immigrants to stigmatise and control them?

Based on the sentencing practices of facilitating unauthorised stay, we can observe the same process in Poland. We see ‘creativity’ of law enforcement in our case border guards, who try to find their way to prevent phenomena perceived by them as contributing to irregular migration phenomena (like international marriages, undocumented work or semi-legal stays) and, by that, to strengthen their control over migration processes. They are creative, and they ‘tailor’ legal provisions differently in different regions to persuade the court to sentence people involved in those processes. However, a few factors inspire us to question the legality of the studied adjudications. A low level of knowledge of migration legislation among Polish judges combined with the rarity of those cases and lack of legal jurisprudence in those matters should be primarily mentioned. Other factors concern the frequent absence of a perpetrator (especially if it is a foreigner) and the simple convenience of work when the case is fully presented to judges by the law enforcement, and no-one will appeal the verdict when it is in accordance with the prosecutor’s demand.

One might say that in the case of migrants and migration offences, ‘the presumption of innocence [is] slowly mutating into a presumption of guilt’ (Guittet and Brion 2017: 92), and, in addition, ‘guilt and imprisonment are based on suspicion, rumour, association, or simply left to the intuitive “gut feeling” of police officers’ (Mantello 2016: 4). Unfortunately, instead of verifying ‘those feelings’ and demanding hard evidence to substantiate them, courts more and more often fail as guarantors of human rights and the rights of the accused. Similarly, they fail to acknowledge the unfavourable position of migrants, unable to see beyond the need to punish them just for violating the migration law or punish their facilitators, whose criminal intent sometimes remains questionable.

Acknowledgements

The research presented in this article is part of the project ‘Ensuring the safety and public order as a justification of criminalisation of migration’, financed by the National Science Centre, Poland, under the grant number 2017/25/B/HS5/02961.

Witold Klaus, Professor of Law, Head of the Department of Criminology, Institute of Law Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences, Nowy Świat 72, 00 330 Warsaw, Poland. witold.klaus@gmail.com

Monika Szulecka, MA, Scientific Assistant, Member of the Department of Criminology, Institute of Law Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences; Nowy Świat 72, 00 330 Warsaw, Poland. m.szulecka@inp.pan.pl

Aliverti A (2012) Making people criminal: The role of the criminal law in immigration enforcement. Theoretical Criminology 16(4): 417–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480612449779

Aliverti A (2013) Crimes of mobility: Criminal law and the regulation of immigration. Abingdon, New York: Routledge.

Ashworth A and Zedner L (2014) Preventive justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bauder H (2014) Why we should use the term ‘illegalized’ refugee or immigrant: A commentary. International Journal of Refugee Law 26(3): 327–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eeu032

Becker HS (1966) Outsiders. Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: The Free Press.

Beck‐Gernsheim E (2007) Transnational lives, transnational marriages: A review of the evidence from migrant communities in Europe. Global Networks 7(3): 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0374.2007.00169.x

Biland É and Steinmetz H (2017) Are judges street-level bureaucrats? Evidence from French and Canadian family courts. Law & Social Inquiry 42(2): 298–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/lsi.12251

Brandon AM and O’Connell M (2018) Same crime: Different punishment? Investigating sentencing disparities between Irish and non-Irish nationals in the Irish criminal justice system. The British Journal of Criminology 58(5): 1127–1146. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azx080

Brouwer J, van der Woude M and van der Leun J (2018) (Cr)immigrant framing in border areas: Decision-making processes of Dutch border police officers. Policing and Society 28(4): 448–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2017.1288731

Bushway SD and Forst B (2013) Studying discretion in the processes that generate criminal justice sanctions. Justice Quarterly 30(2): 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2012.682604

Camillo CA (2017) Street-level bureaucracy. In Farazmand A (ed.) Global encyclopedia of public administration, public policy, and governance: 1–5. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_654-1

Castles S (2004) The factors that make and unmake migration policies. The International Migration Review 38(3): 852–884. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00222.x

D’Aoust A-M (2013) In the name of love: Marriage migration, governmentality, and technologies of love. International Political Sociology 7(3): 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12022

Dauvergne C (2013) The troublesome intersections of refugee law and criminal law. In Franko Aas K and Bosworth M (eds) The borders of punishment: Migration, citizenship, and social exclusion: 76–90. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dekkers T, van der Woude M and Koulish R (2019) Objectivity and accountability in migration control using risk assessment tools. European Journal of Criminology 16(2): 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818771831

Dworkin R (1977) Taking rights seriously. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Foucault M (1977) Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York: Vintage Books.

Gruszczyńska B, Marczewski M and Ostaszewski P (2014) Spójność karania. Obraz statystyczny stosowania sankcji karnych w poszczególnych okręgach sądowych. Warsaw: Instytut Wymiaru Sprawiedliwości.

Guittet E-P and Brion F (2017) The new age of suspicion. In Ekhlund E, Zevnik A and Guittet E-P (eds) Politics of Anxiety: 79–99. London, New York: Rowman & Littlefield International.

Hamlin R and Mellinger H (2018) The role of courts and legal norms. In Weinar A, Bonjour S and Zhyznomirska L (eds) The Routledge handbook of the politics of migration in Europe: 99–108. London, New York: Routledge.

InfoCuria (2016) Info Curia. https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf;jsessionid=890B4014A9240730A2BA537AA77A8490?text=&docid=178802&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=12303466

Jandl M (2007) Irregular migration, human smuggling, and the eastern enlargement of the European Union. International Migration Review 41(2): 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00069.x

KGSG (n.d.) Statystyki SG. Komenda Główna Straży Granicznej. https://www.strazgraniczna.pl/pl/granica/statystyki-sg/2206,Statystyki-SG.html

Klaus W (2017) Security first: The new right-wing government in Poland and its policy towards immigrants and refugees. Surveillance & Society 15(3/4): 523–528. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v15i3/4.6627

Klaus W (2020) Between closing borders to refugees and welcoming Ukrainian workers: Polish migration law at the crossroads. In Goździak EM, Main I and Suter B (eds) Europe and the refugee response: A crisis of values?: 74–90. London and New York: Routledge.

Królikowska J (2020) Sędziowie o karze, karaniu i bezkarności. Socjologiczna analiza sędziowskiego wymiaru kary. Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Kubal A (2013) Conceptualizing semi-legality in migration research. Law & Society Review 47(3): 555–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/lasr.12031

Lipsky M (2010) Street-level bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the individuals in public service. New York: Russel Sage Fund.

Macías-Rojas P (2016) From deportation to prison: The politics of immigration enforcement in post-civil rights America. New York: New York University Press.

Mantello P (2016) The machine that ate bad people: The ontopolitics of the precrime assemblage. Big Data & Society 3(2): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716682538

MoJ (2019) Statystyka sądowa—Prawomocne osądzenia osób dorosłych w latach 2013–2017 (a także osądzenia w I instancji sądów powszechnych 2018). Ministry of Justice. https://isws.ms.gov.pl/pl/baza-statystyczna/publikacje/download,3502,18.html

Okólski M (2000) Illegality of international population movements in Poland. International Migration 38(3): 57–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2435.00115

Perry M (2003) Protecting human rights in a democracy: What role for the courts? Wake Forest Law Review 38: 635–696. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.380283

Reyes MI (2012) Constitutionalizing immigration law: The vital role of judicial discretion in the removal of lawful permanent residents. Temple Law Review 84: 637–700.

Rude-Antoine E (2005) Forced marriages in Council of Europe member states. A comparative study of legislation and political initiatives. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Ruhs M and Anderson B (2006) Semi-compliance in the migrant labour market. COMPAS Working Paper No. 30. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.911280

Rzeplińska I and Włodarczyk-Madejska J (2018) Przestępczość cudzoziemców w Polsce na podstawie danych policyjnej statystyki przestępczości za lata 2013–2016. Studia Prawnicze (4 [216]): 137–163. https://doi.org/10.37232/sp.2018.4.4

Sklansky DA (2012) Crime, immigration, and ad hoc instrumentalism. New Criminal Law Review 15: 157–223.

Stumpf J (2006) The crimmigration crisis: Immigrants, crime, and sovereign power. American University Law Review 56(2): 367–419.

Szulecka M (2016a) Paradoxes of formal social control. Criminological aspects of foreigners’ access to the Polish territory and labour market. Biuletyn Polskiego Towarzystwa Kryminologicznego im. prof. Stanisława Batawii (23): 79–95.

Szulecka M (2016b) Przejawy nielegalnej migracji w Polsce. Archiwum Kryminologii (XXXVIII): 191–268.

Szulecka M (2017) Wybrane zagrożenie migracyjne w Polsce w ujęciu koncepcji naznaczania społecznego. In Buczkowski K, Klaus W, Wiktorska P and Woźniakowska-Fajst D (eds) Zmiana i kontrola. Społeczeństwo wobec przestępczości: 97–122. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe ‘Scholar’.

Tata C (2007) Sentencing as craftwork and the binary epistemologies of the discretionary decision process: Social & Legal Studies 16(3): 425–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663907079767

Thomas D (2003) Judicial discretion in sentencing. In Gelsthorpe L and Padfield N (eds) Exercising discretion. Decision-making in the criminal justice system and beyond: 50–73. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

Tillyer R and Hartley RD (2010) Driving racial profiling research forward: Learning lessons from sentencing research. Journal of Criminal Justice 38(4): 657–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.04.039

Trčka M, Moskvina Y, Leontiyeva Y, Lupták M and Jirka L (2018) Employment of Ukrainian workers with Polish visas in the Czech Republic: From the main patterns of labour exploitation towards points of intervention. Prague: Multicultural Center Prague. http://www.solidar.org/system/downloads/attachments/000/000/841/original/Employment_of_Ukrainian_Workers_through_Polish_visas.pdf?1542195590

Vankova Z (2020) Circular migration and the rights of migrant workers in Central and Eastern Europe: The EU promise of a triple win solution. Cham: Springer.

Vermeersch P (2005) EU enlargement and immigration policy in Poland and Slovakia. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 38(1): 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2005.01.006

van der Woude M and van der Leun J (2017) Crimmigration checks in the internal border areas of the EU: Finding the discretion that matters. European Journal of Criminology 14(1): 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370816640139

Zedner L (2007) Preventive justice or pre-punishment? The case of control orders. Current Legal Problems 60(1): 174–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/clp/60.1.174

Legislation Cited

The Act of 6 June 1997 (Poland)—Criminal Code. Journal of Laws of 2020, item 1444 (consolidated text with further amendments).

The Act of 6 June 1997 (Poland)—Code of Criminal Procedure. Journal of Laws of 2021, item 534 (consolidated text).

Council Directive 2002/90/EC of 28 November 2002 defining the facilitation of unauthorised entry, transit and residence. Official Journal L 328, 05/12/2002 P. 0017–0018.

Council framework decision 2002/946/JHA of 28 November 2002 on the strengthening of the penal framework to prevent the facilitation of unauthorised entry, transit and residence. Official Journal L 328, 05/12/2002 P. 0001–0003.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/IntJlCrimJustSocDem/2021/31.html