|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Law, Technology and Humans |

Institution and Abyss

Thomas Giddens

University of Dundee, United Kingdom

Abstract

Keywords: Pierre Legendre; graphic justice; legal theory; horrific jurisprudence; Nod Away; form.

To be a legal subject is to be held in a nest of institutional forms amidst an unending sea of absence. This is the story that law tells us—its founding myth. The institution of law divides its subjects out of the continuity of the universe, erecting and narrating a symbolic order, a system of forms that masks ‘the fantastic beyond of institutions’, [1] pacifying and subjectivating the individual. To live with respect to law is to be institutionalised—to be captured, comforted, and contained; screened off from the imagined exterior; kept safe from the abyss; protected from the chaos and monstrosity of a universe without order. In this sense, subjecthood and lawful relations are constituted or enabled by concealing that which remains outside the material confines of legal (juris-) speech (-diction) in its broadest sense. To better understand this process of institutionalisation, this paper works to articulate the way everyday material legal forms operate on a psychic or ideational level, the way the ‘mystical’ body of the law rides upon its material one,[2] delineating what we might term the ‘jurisdiction of presence’.

To do this, it uses the psychoanalytic jurisprudence of Pierre Legendre, Joshua W Cotter’s enigmatic comic Nod Away,[3] and the nominally fictional work of HP Lovecraft to reflect upon institutional form. It examines the way law’s powerful bureaucracy is elaborated against the backdrop of an unregulated or undivided cosmos, approaching the emblematic phrase ‘institution/abyss’. The paper thus has three main sections—‘Institution’, ‘/’, ‘Abyss’—across which the narrative moves. The first section describes a distinctly institutional form of law by engaging with the historical development of law reporting. Law reports are an exemplary site of institutional legal presence. However, they rest upon an understanding of material legality as the hermeneutic of a law that is always located elsewhere. The next section then shifts to law’s founding division, the ‘/’[4] that enables legal form to emerge or become present. This is explicated through engagement with Cotter’s Nod Away and Legendre’s God in the Mirror.[5] Cotter presents a space station institution floating in the abyss of space, and this is read as an emblematic figure of law’s founding division from absence as articulated by Legendre. Finally, the paper reflects on the breakdown of this founding division, which is signalled aboard Cotter’s space station when a squiddy monstrosity breaks through from the void. In encountering this breach, Lovecraft’s dramatic explorations of the unspeakable horror beyond the limits of representation are used to frame Cotter’s more pensive gestures towards the contingency of form that otherwise permeate the multiframe of his work.

This is a trajectory that is characteristic of a ‘horrific jurisprudence’—a mode of legal thought preoccupied with law’s reliance upon the idea of a (suppressed) infinite or unknowable context, and how engagement with this context might be understood to progressively challenge the conscious order(s) of legality.[6] Ultimately, law will be observed as the articulation of knowable structures that are narratively separated from an unknowable context, made present to us through the material phenomena that distribute sovereignty and ‘hold’ the subject in its nest of forms, while at the same time staging the suppression of that which lies beyond its limits. The paper thus closes with an aphoristic vignette of law as the ‘commodious apartments’ described by Blackstone, but set adrift in the unspeakable seas of the cosmos—as represented by Nod Away’s space station institution, as well as by the figure of the archetypal comics panel itself: a consciously inscribed space, delimited and located amid the material blankness of the page.

Institution

Law may consist of many divisions and subdivisions in its conceptual structures, as a multiframe of atemporal and interrelated elements, ‘a database aesthetics ... [that we] activate and inhabit’[7] as we do the formal structure of comics.[8] But its ideational structure—its ‘geography of mental spaces’[9]—is enabled by, or anchored to, the material forms of institution. While law reports are one of the most privileged institutional forms of law, prior to the advent of reliable reporting the oral or performative court experience was the primary institutional site where law could be encountered. Indeed, law reports sit amidst a range of artefacts and material inscriptions via which law might be found: statutes, of course, but also architecture, theatrics, dress, symbolism, road signs, and so on. However, without the interpretive encounter of jurists, these institutional ‘texts’ (understood in the broadest possible sense) remain as dead matter. To paraphrase Miguel de Unamuno: once the law is torn from the heart and poured out in text and there fixed in unalterable shape, it is already only the corpse of the law.[10] But from there to be reanimated through interpretive endeavour, to be raised as Frankenstein’s monster or as a zombie or spectre, to walk again as law in the mind of another. In such a phrasing, law reporting is the practice that ostensibly seeks to display the institutional corpse of law for consumption and reanimation by jurists. Put more conventionally, it is through interpretation that the legal authority of a material source is built and deployed.[11]

The question of law’s location can be observed in the core material practices of the common law; the historical emergence of written law reporting is permeated with questions about the source of legal principles and pronouncements. During the 13th century, law reporting took its embryonic steps in the central courts of the English legal system. The Year Books, as they are now known, contained written records of the oral arguments presented in the Court of Common Pleas,[12] the royal court to which matters of procedure were referred from the wider system of lay juries and landowners spread across the country.[13] Given the preponderance of procedural matters, the Year Books were not concerned with doctrine and ratio decidendi, but with capturing and transmitting the developing techniques of the pleader’s art: the ‘occult science’[14] of argument at the most elite level of technicality.[15] They were educational tools for the small number of individuals who oversaw centralised juridical administration and the primary means by which this information was circulated.[16] The ‘reports’ of argument in the Year Books were not a collection of binding precedents,[17] but an applied manual of rhetoric: a technical guide to argumentative practice. Indeed, many early legal treatises followed the same purpose as the emergent texts of law reports, with both being compiled as educational tools for aspiring lawyers[18]—materially inscribed spaces to be inhabited and activated on one’s journey towards lawyerly subjecthood.

Yet alongside this pedagogic function, the Year Books also ‘revealed the law that was being manufactured by the pleading process’,[19] thereby communicating the common law as a ‘by-product’[20] of demonstrating rigorous argumentation. Despite this, law was not understood to be contained or expressed by the reported text,[21] not least because reports did not have the trusted authority of court records.[22] However, even court records were not a normal part of legal argumentation up to the 17th century and were known to be rejected by judges who disagreed with them.[23] Law was thus not to be found in the recorded decisions or the material scribblings of those who happened to witness the court’s proceedings.[24] Instead, it was in the embodied praxis and the learned knowledge of the ‘practical men and specialists’ who made up the highly exclusive group of pleaders and judges,[25] and who alone inhabited the living spaces of institutional adjudication.

The later advent of print technologies in legal writing—technologies to which access was limited—solidified the exclusive quality of this unwritten law into the new legal texts (both commentaries and reports). This ‘reaffirmed the established order of the legal institution and its presentation of writing as governed by a dogmatics of the unwritten word’.[26] It was not until well into the 17th century, as reporting became more trustworthy (in part due to the increased reliability of printed reports),[27] that something like the idea of stare decisis took hold, with judges only starting to take responsibility for the reported form of their decisions over a century later.[28] However, this evolution was not understood to relocate law within the text: as Lord Mansfield remarked in the 1774 case of Jones v Randall, ‘the law of England would be a strange science indeed if it were decided upon precedents only’; legal principles are encoded into text only to ‘illustrate’ them, or try ‘to give them fixed certainty’,[29] and are thus imagined to inhabit a space outside the written record.

When it comes to the material form of the common law, its appearance ‘represents an invisible presence, it manifests a deep structure or law which otherwise escapes the senses’.[30] In this way, the emergence of law’s written form involved the development of a material system for the inscription (and thence governance) of social values and communal relations, but these inscriptions were never imagined to be the law itself. Law was to be found in the material spaces, effects, and practices of the institution, or somewhere beyond material forms—and it is by maintaining law outside its written sources that the exclusive authority of these sources can be preserved. For instance, Peter Goodrich examines the genealogy of written law in terms of its connections with the inscriptions of heraldry that underwrote dominant social hierarchies with a divine order. He traces this practice through to the development of inscribed writs and other material legal instruments that similarly took their authority from a source outside their sensible form.[31] He frames this structure of legal authority more generally in his classic work, Reading the Law:

[The beyond] represents the foundation of law—in theology, politics or myth—yet paradoxically, this ideational source is always a deferred or absent source, it is always in its nature hidden rather than explicit, abstract rather than readily available, past rather than present.[32]

It is the obscure dimension of law that provides the legitimating source of the legal order and the meaning of its marks. For Goodrich, this beyond is imagined as the immemorial tradition or divine authority of the common law that restrains the (legitimate) meanings of its language.[33] Law’s authority is thus invested in the beyond of its texts, with this beyond being a dogmatic space of origin that predetermines the legal order in advance of its inscription and interpretive encounter.

Law—if it exists—is not contained or captured in its institutional texts or presentations. Instead, these forms transmit or enable its fleeting apprehension, or metaphorise its potential existence elsewhere. But while there may be some debate regarding situations where institutional law is suspended,[34] on a material level there is always an inscription at play in the physical articulation of legal authority.[35] As Andreas Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos points out, law is a ‘material metaphor’ that ‘refuse[s] to separate matter from language’;[36] it is always grounded in space and material presence.[37] Sovereign authority, articulated in law, is always enmeshed with the material forms of inscription that mediate it:

Law as an abstract universal, free from the constraints of matter and bodies and space is one of the illusions that law itself (and some strands of legal theory) insist on maintaining ... [but] it is only through its very own emplaced body that law can exert its force.[38]

Following this logic, if the immaterial ‘elsewhere’ from which law springs is an illusion, then legality becomes coextensive with the material forms themselves—without reference to an origin or source: ‘only from within matter can law control.’[39] It is in this sense that Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos conceives of law as flesh:

neither just a thing nor just a concept, flesh is the parallel co-existence of both legal matter and legal language, brimming with legal texts, statutes, decisions, opinions, symbols, but also bodies and spaces that would seemingly be outside the usual symbolic expanse of the law, yet in reality they are in the core of what it means to be legal.[40]

As the emergence of law reporting shows, law is traditionally imagined to lie beyond or external to its texts or material objects: the various forms of law mediate it, enabling access or conceptual elaboration. Acknowledging this external source as an illusion collapses law into its material presence, the authoritative effects of which can no longer be secured by reference to a beyond but instead can be understood to operate through the manipulation of an atmospherics that hides the immanent spatial presence of law.[41]

We thus have two possible locations for law, neither of which consists of the ‘primary sources’ produced by the state institution: law is either everywhere, or nowhere. It is always coextensive with its material inscription (be that inscription in words, architecture, symbolism, dress, ritual, or any other perceptible form), or is imagined to always escape or lie beyond it. Law is here, in its material presence, or it is there, elsewhere, outside its material form. Law is here or there, this or that. In either case, the institutional ‘sources’ of law do not contain or express ‘the law’ itself: either they are a small part of the material presence of law that runs throughout the spaces of the world (the ‘lawscape’[42]), or they are a hermeneutic of an inaccessible law that comes from (an illusory) beyond. In either case, we are left only with law’s material forms of inscription as possible sites of legal encounter. Through procedures of reading, hearing, or deciding, judges form the law on an ideational, conceptual, or imaginary level before seeking to capture, express, or inscribe it in material form—and then it is gone, lost, only accessible via an interpretive or reanimating encounter with its trace, its performative embodiment, the texts, items, or subjects of its inscription. Either these inscriptions make up language (broadly understood) that, while not necessarily coterminous with the law, is necessary for its material expression and effects, or they are part of the immanent materiality of law itself.

The idea of a unitary source of law recedes from view,[43] and the primacy of institutional forms are disturbed, becoming single examples within a wide range of material forms that law might appear within, as, or through. This is an important premise underlying the approach of cultural legal studies, which reads law and justice across the plethora of culture’s material forms—from statutes to cinema, court records to comics.[44] Nevertheless, the institutional form of law (textual or otherwise) remains an important one within society and culture. It is a leading site of the cultural expression of normative meanings and the dominant emanation of legality that constitutes subjects under sovereignty. It is the form that is most consciously appropriated by sovereign power, the one that claims to wield the most overt and legitimate authority. It thus remains an important form of law, a key fold within the lawscape, and one whose form qua form, whose specific material elaboration, requires detailed scholarly attention. It is the emergence or elaboration of this particular form of law, and its structural reliance upon the idea of division from its posited beyond, that this paper examines—through engagement with the comics work Nod Away.

/

If it separates us from anything, the material form of law separates us from law’s unmediated source—its formless form. This divisive quality trickles through the many layers of the legal edifice: be it the othering of criminals; the description of the contours of acceptable conduct, relations, or promises; distinguishing cases; the delineation of rights and the subject who can bear them; or—indeed—simply describing a geographic jurisdiction via the sovereign cutting of space.[45] It is this complex array of divisions that constitutes the legal multiframe—the nested, atemporal, database aesthetic made up of the network of legal pronouncements.[46] Law then ‘conjures up meanings for the spaces on either side’ of its various boundaries.[47] The most profound level upon which this division takes place—and which can be said to enable all those other, smaller and more everyday divisions—relates to the technically radical (from the Latin radicis, ‘root’) separation of form from formlessness, of presence from absence. As legal subjects, constituted or enabled by the materiality of the legal multiframe as it distributes sovereignty, we are separated not only from law’s unmediated form but also from the non-inscribed continuity of the universe. The ‘synecdoches of sovereignty’[48] that make up law’s material expressions (documents, courtrooms, police uniforms, ritual performances, prison architecture, or any other player in law’s ‘theatre of emblems’[49]) keep us contained and protected. Docile, you might say—subjectivated by the elaboration of institutional forms.[50] Or, put in various different ways: separated from the unregulated and unnameable expanse of the cosmos, from the void beyond the boundary of (legal) presence, or from the continuum beyond the institutional fold of the lawscape,[51] the endless other frames of the multimodal multiframe of knowing.[52] Following Legendre, it is this boundary between the presence and absence of the institution, between regulable existence and the world without order, that is fundamental to understanding the radical elaboration of institution. And this section is concerned with precisely this boundary, as elucidated by the formation of institution explored in Nod Away.

Cotter’s Nod Away, published by Fantagraphics in 2016, is the opening gesture of a projected seven-part science fiction epic.[53] Cotter claims it is fully planned out, just not yet drawn—at the time of writing, Volume II is still in production, and the individual labour involved in rendering this intricate comics work is almost as expansive as its conceptual scope.[54] The complete Nod Away exists in potentia, as an idealised work that (in de Unamuno’s terms) is yet to be rendered a corpse on the page. Unable to access this unresolved opus in its entirety, this paper focuses on the rasterised first volume—which, as an opening gesture, is preoccupied with the question of formation. This preoccupation, combined with the institutional substance of its central narrative, makes it a valuable resource for critically articulating the primal division that law relies upon to found its institutional expression.

Nod Away is set in space, on a station orbiting the Earth, adrift in the cosmos. More specifically, it is set within the institutional structure aboard that orbital station—it depicts an institution floating in the abyss. The lead character is scientist Dr Melody McCabe, who has been invited to work in the space station’s laboratory to help administer a technology called ‘streaming’. This technology enables individuals, via neural implants, to connect their brain or consciousness to a version of the internet. These basic narrative features already expose some substantive concern with boundaries against an expansive beyond, and with the transgression or disruption of material limits—a suspicion that plays out spectacularly across the volume’s narrative.

The space station environment that Cotter inscribes is a closely crafted institutional space. Upon entering the station, McCabe is confronted with a range of characteristically bureaucratic frustrations. Note Figure 1, for example: despite her physical presence, McCabe is told by the helpful receptionist that she has not yet arrived. McCabe’s in vivo appearance does not match the expected date contained in the station’s bureaucratic files. This reveals an early emanation of the division between structure and beyond that the broad features of the narrative signal. The ‘fileworld’ takes precedence and replaces the ‘real’ world it seeks to administer, thus dividing the institutionalised subject from the continuity of the Real.[55] Later, McCabe has a headshot taken for an ID card, enabling her docile body to be tracked within the institutional hierarchy;[56] for example, when militarised guards verify McCabe’s credentials before permitting her entry to the laboratory space where she works.[57] Aboard the space station, then, McCabe is not just inside an Earth orbital station, but is also within the confines of an institutional structure, the material encoding of a conceptual geography—rasterised ideology that she must navigate via appropriate protocols and submissions.

Figure 1. From Cotter, Nod Away, 52. Copyright, 2016, by Joshua W Cotter.

The work of Cornelia Vismann examines this imbrication of institutional materiality with the operation of legal power. Files may be the central mechanism of sovereign power, with the history of the modern state being meaningfully told as a story of the proliferation of filing technologies,[58] but other objects also demonstrate the material articulation required for sovereignty to operate. Vismann terms this articulation ‘cultural techniques’,[59] and one example she examines is the humble table:[60] an object that is found in all courtrooms and without which legal processes would struggle to take place. Vismann claims the material presence of the table grants access to a procedure of justice:

Judges’ decisions are binding and enforceable precisely because there is a power in the background that underwrites them. The state grants the verdict force of law. Without a table, conflicting parties meet one another as two antagonistic sides without reference to a higher third party.[61]

In this vision, by giving a physical setting within which a dispute can play out, it is the table that provides the powerful presence of the state that underwrites the judge’s decision and enables the practical procedures of law to function. Mundane material objects such as files and tables (as well as chairs,[62] reception desks, ID badges, and military uniforms) shape and delimit what we understand law and justice to be: ‘What truth is, what the idea of justice is, manifests itself in such humble technologies’.[63]

Despite these features, the institution in Nod Away is not overtly a legal institution. Except for the arrival of two Interpol agents towards the end of the narrative, there is little in the way of traditional legal trappings: no judges, courts, police, or legislature—not even a law report. It is more apparently a corporate institution; superficially a private rather than a public structure. However, Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos unpacks the immanent tautology of law and space, beyond Vismann’s specific concerns with institutional technologies, tracing the presence of legality throughout the world of material objects.[64] This is an understanding that would automatically render Cotter’s institution legal despite its ostensibly private quality. However, Cotter’s institution can also be connected to state law by acknowledging that, despite the efforts of neoliberalism to roll back governmental control in favour of a form of self- or auto-regulation by the market, the core hierarchical principle of sovereignty (archism) actually escapes the confines of the state to circulate through the hierarchies of commercial structures.[65] Thus, the material closure of the space station expresses the closure of McCabe as a distinctly institutional subject.

McCabe’s institutional closure is clearly articulated through Cotter’s manipulation of the comics form. An early and profound encoding of the play of closed, intricate form against the expansive cosmos is presented during McCabe’s shuttle flight to the space station. She is seated next to a well-meaning but increasingly chatty old lady, with her companion’s speech-text gradually taking over the panels, leaving less and less space for McCabe. Cotter’s cramped style helps develop the claustrophobic experience, until eventually an elegant transition is made from inside to outside the shuttle: the reader turns the page from the heavily inscribed interior to a vast, borderless double-page of mostly black expanse, dotted with stars, against which floats the space station—the USS Integrity (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. From Cotter, Nod Away, 48–49. Copyright, 2016, by Joshua W Cotter.

This particular transition is important for its rarity—the cosmic expanse is not often shown, with most of the pages filled with Cotter’s intricate inscriptions of internal spaces. This early shift from heavily delineated interior to undifferentiated exterior sets the scene for what follows: an almost exclusive exploration of the closed form of the institution aboard the space station.[66] And combining the archist institutional structure in Nod Away with its (suppressed) cosmic setting, we can read it as an expression of the material hierarchies that subjectivate the individual under sovereignty—but explicitly situated within the abyss of space. Cotter’s work thereby becomes a meditation on the confines of institutional life against a background of openness or limitless expanse, but at the same time remaining sensitive to that infinite context in or against which institutional structures take shape or otherwise become elaborated, how they ‘rupture’ immanent materiality in order to delineate the folds of the institutional assemblage, the pocket of the institution, within the continuum of the lawscape.[67] In this way, Cotter’s work enables an encounter with the founding or radical division (or rupture) that makes the institution of law possible.

In God in the Mirror, Legendre attempts to textually articulate the mechanics of the division between presence and its beyond—a division that not only enables all discourse and culture but is also a distinctly legal phenomenon, bound up with questions of representation, subjecthood, and normativity.[68] It is the separation of the orders of language, representation, speech, sense, awareness, experience, and so on—from a realm of absolute absence or alterity. To put it in Vismann’s terms of the technologies that enable cultural articulation:

The counterpart of cultural techniques ... is a world where techniques do not exist at all, a notion which cannot even be mentioned without using yet another cultural technique: the act of naming, which allows things to be used and studied in the first place.[69]

This uncommunicable alterity is perhaps best rendered textually as

‘ ’.[70]

It is that about which it is not possible to say anything at all, which is

impossible to describe or cannot in any sense be presented.

In Derridian

parlance, it is the outside-text, the nothing outwith the realm of

inscriptions—that which is uninscribed and

thus absent to human encounter.

To speak of it always involves some form of representation, some ‘cultural

technique’,

that in its presence replaces the absence it seeks to display.

Absence, perhaps. One of the terms that Legendre uses to

express this beyond is ‘the absolute’, tracing its etymology to the

Latin ab, meaning ‘from’, and solvere, meaning without

connection or contingency: the absolute comes from somewhere

‘unbound’.[71]

Free from the ‘indetermination’ of the symbolic

order,[72] the absolute does not

rest upon any human contrivance or structure of knowledge but emerges from

without context—from beyond,

from

elsewhere.[73]

For the elaboration of institutional forms to be possible, and thus for a

normative order to be articulated, the distinction from

‘ ’

must be staged. Legendre’s study clarifies that staging this divide is the

central work of myth.[74] Myths

enable us to grasp our separation from absolute alterity, from the beyond about

which we cannot know or speak. They are a ‘representation

of Nothing

[that] sustains every representation of the world ... and [the] presence of the

subject to the world’.[75]

They stage this division in discourse and—as discourse

themselves—are grounded upon the very division they narrate, providing

a

reflexive management or ‘handling’ of the cut from

absence.

Before form can be articulated, there must be a separation from the abyss beyond all forms, and cultures handle this division through their myths. However, as Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos reminds us, this staged division is the ‘necessary illusion’[76] needed to understand the world as singular and univocal. ‘The negative is not the precondition for the world’,[77] yet we hold onto the ‘fragile, balmy, infinite illusion’ of an outside.[78] Law’s founding divide is a ‘rupture’ in the continuity of the world that renders it comprehensible[79] by constructing an inside/outside division within the world itself.[80] In this sense, Legendrean myths become the source code of culture:[81] the opening gambit of discourse, the necessary ideational foundation upon which all articulable meaning is built. ‘We need ruptures’, as Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos puts it.[82]

The introductory sequence of Nod Away mythically stages its own

formative division from

‘ ’.

Its first transition is between a blank white verso

page and a blank white recto

page containing a single, small dot. This transition is key because it is a

transition from absence

(blankness) to presence (dot). In this transition the

radical cut from absence is articulated, and in this movement

form and content appear

simultaneously,[83] a duality of

‘emergence’ and

‘monstration’[84]—of

that which appears, and that which it communicates. These ‘two

indissociable planes of representation and

discourse’[85] appear

together: the first (structure or form) describes the locus of the absolute and

the division from the beyond; the second (content

or discourse) provides the

narration of that limit, indicating the edge of possible

speech.[86] While Cotter’s

opening transition begins this narration, and it is possible to conceive of the

dot as substantive content rather

than bare form, his opening pages continue the

staging more explicitly. The dot becomes the dot of an ‘i’, then

other

letters appear, and grow, and spread across the page, accumulating

representational forms page by page until the material space of

the paper is

crowded with overlapping, densely shaded shapes (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. From Cotter, Nod Away, 13.

Copyright, 2016, Joshua W Cotter.

Figure 4. From Cotter, Nod Away, 14.

Copyright, 2016, Joshua W Cotter.

A second key transition takes place between pages 13 and 14, culminating the mythic narration in a way that suggests a self-awareness of form (see the transition between Figure 3 and Figure 4). The letters and shapes turn blank, with only their outlines remaining—the mere limits of their articulation. Concurrently, the word ‘limit’ becomes perceptible in the centre of the page. Form and content appearing together: the structural outline and the articulation of discursive content (‘limit’), which itself narrates the formation of the structure. It is an arrangement of limits that communicates the limit of discourse. The simultaneity of these levels is necessary precisely in order to stage the foundation of discourse: we articulate the world via ‘mediation of the scene of the absolute’ alongside ‘the speech which envelops it’.[87] It is not just that discourse is separated from its beyond, but that it reflexively narrates its own division from that beyond, thereby maintaining the illusion of this beyond and securing discourse within the realm of presence.

In this way, the originary formation of representation is a revelation, with ‘reveal’ being understood as a compound of res (thing) and velare (to veil or hide). For Legendre, to reveal is not simply to uncover or show, but to show something by hiding what is shown.[88] In the context of the staging of the absolute beyond, this becomes a representative form or cultural technique that refers to the outside of representation, simultaneously masking and acknowledging, just as the printed letters of ‘absence’ mask and acknowledge ‘ ’. Put reductively: masking with form, acknowledging with content.

Figure 5. From Cotter, Nod Away, 22. Copyright, 2016, Joshua W Cotter.

Cotter’s opening sequence progresses from the idea of communicative

form itself to the specific form of comics. The first formal

comics panel

appears on page 22 (see Figure 5). It continues the mythic function of the

opening sequence by presenting a single blank

panel placed over a textured and

undifferentiated background with the word ‘limit’ inscribed inside

it, connecting this

archetypal piece of comics nomenclature to the founding

limit that the work has already affirmed. With this, Cotter demonstrates

that

the comics form is predicated upon a division—the delineation of the space

of the page into identifiable, separable

units[89] that enable the

articulation or conceptual elaboration of

meaning.[90] And, moreover, that

this division echoes or rests upon a more primal division of presence from

‘ ’.

Accordingly,

the word ‘limit’ placed inside the delimited space

repeats the dual appearance of form and content, bringing forth the

way comics

makes the contingency of form upon absence explicit. As Adam

Gearey notes, in the comics form:

inscription exists against a blank space—a space that might act as a repository for ideas that are yet to be thought and for events that might change interpretations. The intervals around inscription mobilize an open and ongoing dialectic where what is, what is not, and what might be, dance with each other.[91]

For Gearey, comics is thus a dialectical dance—between absence and presence as much as word and image. Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, meanwhile, seeks to avoid such a dialectic between presence and absence in favour of their ‘co-emergence’.[92] In this sense, the inside and outside become ‘folds’ in the continuum[93] and the inside ‘becomes other by bringing everything within’.[94] Cotter indicates a similar instinct on page 23, where he captures something of the way the ‘outside’ is folded into the ‘inside’, or—put in more Legendrean terms—how the infinite beyond is always a necessary part of perceptible form: ‘infinity’ is located ‘in’ the comics frame (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. From Cotter, Nod Away, 23. Copyright, 2016, Joshua W Cotter.

Indeed, Figure 6 could be considered an ‘emblem’ of the void, which Legendre defines from its Greek roots (emballo) as that which ‘throws signs inside ... [so that] the Nothing enters lingual space’.[95] In this way, discourse ‘whittles down the abyss with enunciations’.[96] Representation can be understood as relying upon the ‘revelation’ (showing/hiding) of its beyond, which is ‘an un-representable, to which symbolic elaborations oppose the universe of speech’.[97] The comics form embodies this, too, as the multiframe ‘throw[s] things side by side’,[98] emblematising the abyss by throwing the blankness of the gutter alongside inscribed frames within an overarching discourse. Comics discourse thus embodies the structural foundations of all discourse, which is ‘at once indefinite in its potentiality and marked by the limit’.[99]

It is in this manner that myth stages the necessary illusion of dividing

presence from

‘ ’,

of form from

formlessness—and, in Cotter’s work, of comics

articulation from blank page. Importantly, this is also the division of

institution from abyss. ‘The quintessence of the symbolic process is

contained in this institutional core: to metaphorise the

abyss, inflict distance

on the subject, institute the category of the

void’.[100] Legendre also

puts this more succinctly: ‘to create the staging of a void

constitutive of

speech’.[101] And this

staging presents a complex montage. It articulates the space of the

void—as beyond, as other—and at the same

time denotes the limit that

divides the void from representation. It thus institutes the universe of

communicable forms—the

idea of representation itself and its

limits—and thereby gives us the normative order of discourse, of

how it is possible or permissible to speak. The radical division between

absence and presence is thus a distinctly legal phenomenon: for

Legendre, the order of representation, of images, is from its very inception

a

legal order.[102]

The divide between presence and its outside thus marks the edge of law’s jurisdiction, or is the place where jurisdiction is established or declared. Daniel Matthews reads jurisdiction as the ‘expressive register of the law’.[103] Where Legendre speaks in terms of divinity or the void, Matthews follows Nancy and locates a necessary communal sociality beyond the limits of legal presence—an originary sociability that comes before and conditions the formalisation of norms into legal speech.[104] For Matthews, jurisdiction is the moment that law emerges from this communal beyond: it is where normativity is inscribed into the material forms of legality. It is the limit of legal transmission, the ‘multifarious ways’ that law’s speech is made manifest[105] and thereby affirms the presence of sovereign authority. ‘The speaking of the law, the announcement of jurisdiction, makes present the legal limit’, rendering the originary normativity ‘visible and readable’; when justice (juris-) is spoken (-diction), the normative order of ius is transformed into lex and the positive forms of material legality appear.[106] Following these lines, jurisdiction becomes implicated in law’s founding myth: it is the ‘fiction at the heart of the law’.[107] It is the ‘comforting voice’[108] of legal presence against its beyond.

Moreover, this elaboration of form is a creative assertion. The declaration

of legal speech is where the law reaches beyond its limit

and folds the beyond

back into itself through perceptible

speech.[109] In terms of the

lawscape, this rendering of jurisdiction is the folding of the illusory outside

into law’s institutional pocket,

or the way the institutional assemblage

becomes other.[110] Put into the

Legendrean frame, jurisdiction is where the law is revealed, where the

incommunicable beyond is emblematised and law’s division from it is

narrated: ‘jurisdiction names those practices

that craft and produce the

law ... [it is] how the law is given shape and

form’.[111] But

Legendre’s claim is larger, and reverses this logic: it is not that

jurisdiction is where law becomes perceptible, but

that appearance itself

marks the limits of the normative order. To be perceptible is to be within

law’s jurisdiction—what we might term the

‘jurisdiction of

presence’. It is in this sense that the legal subject is held within a

material jurisdiction, a nest

of forms. The presence of institutional law is

contingent upon the division between absence and presence in

general, but that division itself is a normative one, permitting possible speech

and providing the set of potential

modules with which an apparatus can be built

and the subject interpellated.

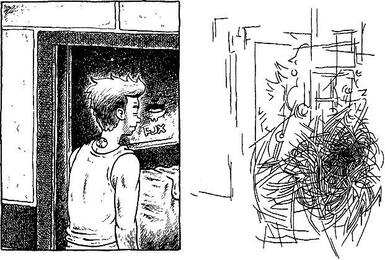

In these terms, what Cotter’s work articulates—founded in the mythic elaboration of its opening sequence and presented explicitly in the early stages of its substantive narrative—is a closely delineated institutional life, navigated by McCabe, and presented against an undivided universe that is paradoxically both immanent and almost completely masked by the material forms of institution. The emergence of Nod Away continues in ever-increasing sophistication from the sequences discussed above, running through the cast of characters enigmatically held in stasis, until eventually the reader is lead into the narrative proper and the USS Integrity is presented afloat in the formless abyss of space. Even once Cotter’s space station institution is fully elaborated and inhabited by its subjects, we still see its foundational division at work. On the USS Integrity, the abyssal background is heavily suppressed—but there are some glimpses of it. One such moment is depicted in Figure 7, when Dr McCabe touches the boundary between the station and outside and tests the limits of her institutional closure.

Figure 7. From Cotter, Nod Away, 58. Copyright, 2016, Joshua W Cotter.

This figure captures much of the complexity of Legendre’s thinking,

particularly the role of Narcissus and the mirror in the

formation of the

institutional subject. In terms of the foundations of discourse that Legendre

and Cotter are preoccupied with, the

deceptively simple act of seeing oneself in

a mirror presents the individual with their own representation and,

simultaneously, the

empirical fact that they are separated from their

representation. The image in the mirror is not them, but is someone (somewhere)

else.[112] By representing the

subject in discourse, institutional law presents individuals with this same

division: the legal subject reflects

the subject back on themselves as a

separate entity, instituting their self-alienation. Legendre highlights that one

does not see

the surface of the mirror itself but only what is reflected in it.

For Legendre, the mirror tends towards invisibility and can thus

be functionally

located outside the realm of presence—on the side of the

abyss.[113] At the foundations of

discourse, Legendre brings together ‘God’ and the

‘Mirror’, absence and our separation from

representations, producing the conflated term

‘third-mirror’.[114]

He thereby distinguishes between two different kinds of nothingness: that which

lies indeterminate in the abyss itself (the

‘

’

beyond the mirror), and that which is instituted as a symbolic category

(the representation of absence in the mirror). The staging of the void

turns one into the other, producing an emblem that throws the abyss inside

discourse.[115]

Just like a space station window, ‘the Mirror serves as a protective screen’ that enables the subject to face the abyss without being ‘engulfed’, and this protective division allows the symbolic order of discourse to emerge.[116] In other words, we look towards the abyss—but we see representations (and thence knowledge) instead. The declaration of the jurisdiction of presence becomes ‘a performative technique of the law’s self-preservation, a comforting voice’ against law’s absence.[117] For Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, this protective impulse is a significant part of what makes the story of an outside necessary:

The outside only becomes relevant through the illusion of distinguishing between interior and exterior. ... We chop up the lawscape in manageable bites of ruptured continuum ... [reflecting] a larger need: to partition the ontological continuum into epistemological ruptures. ... All ruptures are ... a defence mechanism that we, conscious human beings, need in order to deal with the immensity of [the] immanence of life.[118]

In Figure 7, Cotter subtly reconfigures this. McCabe looks through the limits of her institutional containment to the abyss beyond, but while it remains a protective screen from the void, Cotter’s depiction replaces the mirror with a window in which we see no reflected image of McCabe. This image thus gently suggests the breaking through of the void, giving a window through the founding division of institutional forms to the endless continuum beyond. This foreshadows the potential return of the abyss, along with an opening of the radical contingency of instituted forms. It is to the modes of this return in Nod Away, and its meaning as a work of horrific jurisprudence, that the next section turns.

Abyss

At the basis of all this stirs the fear of thinking a category of the void, fright before the human condition to which every institutional scaffold remains riveted in the West as everywhere else.[119]

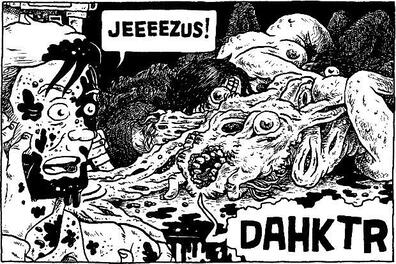

Law’s speech is a comforting voice against the outside of the jurisdiction of presence, the pacifying forms of institution that keep the subject contained within its limits. As comics-philosopher Tom Kaczynski frames it in his one-page ‘White Noise’, it is the hum of discourse that soothes and protects humanity from the beyond.[120] In this light, the attempt to think beyond boundaries, to access law without its material form, can be framed as horrific—or as opening up to a form of madness. As Blandy and Sibley note, ‘we could associate psychotic anxiety with a desire to close off and separate from the outside’, no doubt caused by the ‘disturbing or unsettling elements’ imagined to inhabit ‘the space beyond’.[121] Nevertheless, as its narrative progresses Nod Away moves inexorably towards a disruption of its institutional limits, and ultimately an overcoming of the fear of such disruption and a concomitant transcendence of the radical boundary itself.

As part of the work taking place on the USS Integrity, an experimental

transport gate is opened to another spacecraft. However, instead of enabling

instant movement between the two gates,

a portal is opened to somewhere

else. We see the eruption from elsewhere in Figure 8, just after the gate

has been opened: a tentacular hand-like appendage appears from

the gate and

squashes a human head with a satisfyingly unpleasant sound effect, somewhere

between a pop and a squelch. This entry

continues until the room is full of an

indescribable organic mass that threatens the lives and beings of those present

as much as

it questions the place of humans within the vast potentiality of the

universe. This indescribable mass is not fully depicted but

consists of hinted

shapes and vaguely recognisable body parts (see Figure 9). After the slow burn

of the bulk of the narrative—with

all its intricate setting up of the

forms and structures of institution, all its mythic work in narrating the divide

from absence in order to secure the presence of the

institutional world, and the gentle pace of pacifying institutional

life—this eruption is both narratively and conceptually

spectacular. The

careful masking of the abyss does not hold. The horrifying beyond bursts forth

in a manner akin to the unknowable

monstrosities of Lovecraftian horror, and the

comfortable forms of subjectivated life are rendered fragile and limited.

Figure 8. From Cotter, Nod Away, 144. Copyright, 2016, Joshua W Cotter.

Figure 9. From Cotter, Nod Away, 147. Copyright, 2016, Joshua W Cotter.

Such ruptures of the jurisdiction of presence are central concerns of a horrific jurisprudence,[122] a mode of legal inquiry that draws prominently from the horror writings of HP Lovecraft. Indeed, to appreciate the reconfiguration of the beyond that Cotter’s work effects, it is necessary to briefly explore the way Lovecraft’s horror writings examine the limits of knowable form. While there are concerns of Lovecraft’s personal prejudice to work through (see below),[123] his body of narrative work, produced across the first half of the 20th century, is ‘centrally concerned with the paradox of representing entities, things and places that are beyond representation’.[124] Accordingly, it can be read as an archive of nominally fictional case studies that present ‘explorations of the limits of language’.[125] The Great Old Ones—Cthulhu and his cohort of gargantuan, unpronounceable beings—are an overt example of Lovecraft’s characteristic brand of horror.[126] However, there are further case studies to be found in the Lovecraftian archive, such as the otherwordly music of Eric Zann[127] or the terrors returning from beyond the grave in ‘Herbert West—Reanimator’.[128] The following passage, found in ‘From Beyond’, exemplifies the radical challenge to human structure and meaning that Lovecraft’s work signifies:

Suddenly I myself became possessed of a kind of augmented sight ... I saw the attic laboratory, the electrical machine ... but of all the space unoccupied by familiar material objects not one particle was vacant. Indescribable shapes both alive and otherwise were mixed in disgusting disarray, and close to every known thing were whole worlds of alien, unknown entities. ... Foremost among the living objects were great inky, jellyish monstrosities which flabbily quivered in harmony with the vibrations of the machine. They were present in loathsome profusion, and I saw to my horror that they overlapped; that they were semi-fluid and capable of passing through one another and through what we know as solids.[129]

As might be gleaned from this passage, to craft proper horror Lovecraft believed that one needed to disturb the ontological foundations of everyday human life: there should be ‘some deeper and more malevolent principle at work in our monsters that escapes all such [everyday] definition’.[130] Accordingly, Lovecraft’s method of ‘unwriting’ pushes at the boundaries of representational language and ‘aims at somewhere which is beyond all narrative structure and possible worlds’.[131] Lovecraft’s horrors thus seek to penetrate the hermeneutic veil of material reality:

Men [sic] of broader intellect know that there is no sharp distinction betwixt the real and the unreal; that all things appear as they do only by virtue of the delicate individual physical and mental media through which we are made conscious of them; but the prosaic materialism of the majority condemns as madness the flashes of super-sight which penetrate the common veil of obvious empiricism.[132]

The Lovecraftian moment breaches the ‘prosaic materialism’ of the everyday world as the infinite and continuous beyond breaks through; the sudden breach of the institutional surface of the USS Integrity presents just such a moment. Lovecraft himself presented this ‘beyond’ as something threatening to the human condition: a terrifying vastness or infinity; an order of beings so completely huge and alien as to render humans and their terrestrial concerns meaningless. As he notes: ‘all my tales are based upon the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large’.[133] A horrific jurisprudence, on the other hand, is not simply about navigating the boundaries of the abyss, but is about embracing their breach. It begins with the anxiety at law’s boundaries and works towards a more progressive formulation of their breakdown. Cotter’s work follows a similar trajectory.

The Lovecraftian moment seeks a movement outside the jurisdiction of

presence. It attempts to make apparent that which is impossible

to articulate on

any level of human experience, to bring forth

‘ ’

and speak the unspeakable from beyond

understanding and our available modes of

being. Ultimately, Legendre’s analysis in God in the Mirror

demonstrates the undoing of foundational myths, or at least provides access to

the work of myth in founding discourse through its

staging and suppression of

the division from absence, its sustaining of the necessary

illusion of an outside. It recognises that knowledge, normativity, and

institution are concurrently

predicated upon both the imposition of form and the

comforting narratives that surround that imposition to handle their division

from the abyss beyond. The Lovecraftian moment operates along a similar

ideological line, but is far more abrupt. It encounters the

dramatic failure of

hermeneutics, the moment when perceptible form breaks down and the

non-communicable breaks through, where the

abyss that discourse works to subdue

returns with a disinterested razing of petty human concerns. Accordingly, the

Lovecraftian moment

does not work to indicate the beyond by unravelling or

working through the structural features of culture’s founding narratives,

nor does it patiently deconstruct the meaning produced within the network of

inscriptions in an effort to indicate that which lies

outside the jurisdiction

of presence. Instead, terrifying entities and indescribable horrors burst

through to consciousness and tear

open the world. The Lovecraftian moment is a

horrific one; not a carefully orchestrated epiphanic revelation nor a patient

scholarship—but

an extravasation of otherness that drowns the waking

world, sending its protagonists mad. Lovecraft’s fiction represents a

neurotic scream[134] against and

within the disruption of ordered, instituted life.

Put in its aesthetic context, the failure of the institutional form in Figures 8 and 9 is one moment within a more complex work that reveals significant insights into the production of institutional form, and concomitantly the material and symbolic elaboration of the sovereign order of law. Cotter’s Lovecraftian moment can be contrasted with other nodes in the multiframe of Nod Away that invoke the outside of presence. Figure 10 shows a dissolving frame, one of several moments when Cotter’s sophisticated formal elaboration of comics disintegrates and moves towards its own vanishing. These dissolving frames occur regularly throughout the volume, at the end of various chapters or sections.[135] Compared to the eruption in Figure 8, this dissolution is a more considered, intricate, or technical coming-forth of the non-differentiated ‘outside’, echoing something of the coming-to-form of the opening sequence. It renders Cotter’s work not merely a repetition of the Lovecraftian method of violently gesturing towards the indescribable, but a more pensive undoing of forms.

Figure 10. From Cotter, Nod Away, 183. Copyright, 2016, Joshua W Cotter.

Indeed, the volume’s ending undoes the entire comics form over a series

of pages that returns it to the blankness of the unmarked

surface with which the

work began, against which every form is affirmed and upon which they remain

contingent. These quiet, disintegrative

moments sit in calm counterpoint to the

spectacular rupture of the tentacular mass that bursts through from beyond the

gate. They

represent an accepting awareness of the contingency of form rather

than the abysmal terror we find in Lovecraft. Taken as a whole,

Cotter’s

work contextualises the Lovecraftian moment within an aesthetic envelope that

remains reflexively aware of the division

from absence that

founds all cultural forms, including its own comics articulation. It takes the

horrific despair that comes with our insignificant,

ephemeral, and precarious

place in the cosmos, and places it within a calm, gentle recognition that,

actually, all forms are fleeting

and contingent upon their relation to things

that lie over the horizon of their appearance. This is not a source of fear but

an important

dimension of human life that enables and maintains our capacity for

communication: the necessary illusions upon which we depend.

This movement away from fear is important. In ‘The Horror at Red

Hook’, Lovecraft lets slip that it may be his terror of an ineffable

beyond that underpins his

prejudices:[136] the belief not

only of an ‘outside’ but, specifically, that the outside is

something to be feared translates the encounter with mundane human

difference into monstrous horror. Fear of the beyond renders ‘old brick

slums and

seas of dark, subtle faces a thing of nightmare and eldritch

portent’.[137] This slip

signifies that it is the distinctly negative or fearful response

to absence that fuels the symbolic refiguration of human

difference into a vast speculative otherness of squiddy nonhuman

monstrosities—in

both Lovecraft’s fiction and his psyche. Donna

Haraway captures this in her characterisation of Lovecraft’s beyond as

his

‘misogynist racial-nightmare

monster’.[138] His monstrous

others have indeed been read as signifying his prejudiced

fears,[139] but his work is also

often read

progressively[140]—as a

horrific jurisprudence also seeks to do. By diffusing the negativity of the

beyond, Nod Away’s horrific jurisprudence potentially undoes

something of the prejudicial dimension of the Lovecraftian moment. In this way,

it joins the numerous examples where Lovecraft has been reframed in a

progressive light. Be it through the romantic nihilism of Lovecraftian

‘chaos magick’, which looks for a better world outwith the stifling

confines of modern reason,[141] or

Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows’s attempted reformulation in

Neonomicon that promises a better future upon Cthulhu’s

return[142]

(yet arguably remains tied up with gender-based

violence[143]), or

Harraway’s own construction of the ‘Chthulucene’ that firmly

rejects Lovecraft and instead absorbs humans

into the vast array of the universe

in a manner ‘that Lovecraft could not have imagined or

embraced’.[144]

Through the horrific jurisprudence of Nod Away, we encounter the question of law’s deepest set of boundaries without the baggage of assuming only bad stuff lies beyond. A horrific jurisprudence takes Lovecraftian horror as its conceptual foundation and extracts jurisprudential value by processing for law the ‘horrors’ that Lovecraft sought to articulate for the human condition: the loss of the necessary illusion of our separation from the beyond, the loss of the ruptures or divisions that we require to articulate meaning and epistemic form.[145] It is a project that works to reframe the beyond invoked by Lovecraftian horror not as a troubling otherness to be suppressed and masked—be it racial or existential—nor as a simple invocation of limits. Instead, a horrific jurisprudence acknowledges the contingency of law’s form and of form itself, of the structural emplacement of instituted materials within the infinite or abyssal context upon which they rely. It is an acknowledgement, too, of the pacifying function served by this material arena, this jurisdiction of presence, that imagines a horrifying beyond in order to keep the individual comfortably subjectivated, nodding away in its nest of forms.

Institution/Abyss

While reading this paper, I am sure the analytical faculties of a certain class of jurisprude may have perked up at the name of Cotter’s institutional space station: the USS Integrity (see Figure 2). For Ronald Dworkin, law is integrity. It is by interpreting the common law with integrity—that is, through a method that ideally moves towards a synthesis of the complete history of the common law, in light of the best possible world the law could hope to enable—that true judicial authority is exercised. There are correct readings of the law, if only one had the capacity of his super-powered Judge Hercules to tackle the entire weight of precedent, the total written expression of the institutional legal order, and thereby access law as a unitary truth.[146] Integrity is a humanist[147] figure for the interpretive coherence of law: it is through a complete reading that legitimate interpretation is properly secured, and law itself is accessed. In such an interpretive model, it is law’s reading practices that hold it together,[148] with Judge Hercules as the mythic force that sits outside the law to give it a unitary order.

Even on a literal level, Cotter’s reference to ‘integrity’

undoubtedly signals a holding together of form. But read

as an exercise in

horrific jurisprudence, the USS Integrity gives us an emblem for

understanding the way the institutional form of law is elaborated against the

abyssal background of undifferentiated

potential. Unable to present its formless

form, the absence upon which it remains contingent, it is the

interpretive endeavour of jurists that gives rise to law’s institutional

trace—the

‘corpse of the law’ epitomised in law

reports—that separates subjects from the abyss. In the figure of

Cotter’s

USS Integrity, we find Dworkin drifting untethered in

space, Judge Hercules floating in the void. Cotter’s image brings forth

the edge of

legal presence and the

‘ ’

upon which it rests; it is a Legendrean emblem, symbolising the radical

elaboration

of institutional form.

The eruption of monsters from beyond challenges the integrity of the institution, threatening its coherence. Andrew Sharpe traces the movement of the monster through the history of legal concepts, highlighting its loss of physical traits and its general internalisation within the legal subject.[149] He thereby shows deviance from legal norms to be a modern formulation of monstrousness: ‘the abnormal individual is ... a figure who bears the monster’s imprint’.[150] Concerns with deviance are thus linked to anxieties about the potential loss of the integrity of law’s conceptual structure, because ‘monsters represent ... a challenge to legal taxonomy’.[151] However, the horror represented by monsters might not be because there are things we cannot know, but because there are things we do:[152] the madness and despair of knowing itself—of being held, contained, or trapped within the maze of rational thought, the jurisdiction of presence; of masking the richness of existence with limited forms.[153] Framed progressively, Lovecraft’s monsters thus become a transcendence of law’s structures, a path to a viewpoint that can see across the radical boundary that delimits the jurisdiction of presence and enables law’s formal structures to emerge. A horrific jurisprudence works towards this transcendence, or at least seeks to encounter the foundation of institutional elaboration. Read this way, Nod Away’s reformulation of the Lovecraftian moment that disrupts the USS Integrity provides fearless, reflective access to law’s founding illusion, opening its institutional form to an immanent and radical potential to be otherwise.

The emblem of institution/abyss captured by the USS Integrity is evident in the writings of Sir William Blackstone. Writing in the 18th century, Blackstone famously presented the common law as an ahistorical and pre-existing structure of true legal rules, a harmonious justice to be found amidst the seeming contradictions and complexities of the written law.[154] However, like the impossible judgment of Hercules, one has to journey through the law’s complexities, to suffer the uncouth noise of legal materiality, in order to reach the harmonious melody of justice—a movement that Blackstone followed in his adherence to the classical ideals of the Concordia Discors that were becoming fashionable again in the 18th century. Like the humanism of Dworkin’s idealised legal procedure, this mode of discourse worked to reconcile contradictions towards the concord of a coherent, unified whole. In Blackstone’s Commentaries, this same ideal was pursued, ultimately translating law’s mysterious complexity into an ordered system.[155] This project masked the cacophony of law’s oral history with the harmony of a singular stream of legal sources:

Blackstone reduces English law’s oral, multi-vocal languages to one harmonious chorus in the Commentaries, quieting the cacophony of voices that undergirded it, replacing them with a supple, almost melodic, surface text.[156]

Blackstone thus attempted to institute a primary and controlling rational order to the alterity of the legal materials amassed over the centuries of legal history that preceded him.[157] Accordingly, in the Commentaries we find him describing the common law as:

an old Gothic Castle, erected in the days of Chivalry, but fitted up for a modern inhabitant. The moated ramparts, the embattled towers, and the trophied halls, are magnificent and venerable, but useless, and therefore neglected. The inferior apartments, now accommodated to daily use, are cheerful and commodious, though their approaches may be winding and difficult.[158]

In this we of course see Blackstone’s idealistic notions of the common law as a venerable truth, steeped in history, but also the results of his own efforts to ‘fit up’ its chaotic mess for the rational tastes of the modern lawyer, to institute the ‘commodious’ apartments of legality against the ‘winding and difficult’ contexts that surround them. Thus, there is an acknowledgement that law is not always clear and certain: it has dark corridors and uncertain forms, which must be navigated to construct or discover the parts that we can properly conceptualise and apply to the vicissitudes of communal life. The law is not simply order, but presents itself as order against disorder, clarity against mystery,[159] reason against madness.[160] Whilst not as stark as Cotter’s freighted presentation of the USS Integrity and its rupture, this passage from Blackstone depicts a modern law that is made up of comfortable apartments embedded amidst unknowable corners and passageways. Thus, even one of institutional law’s most celebrated apologists saw that modern law consists of knowable forms within an unknowable context; that law is comforting certainty rendered against a vast and complex uncertainty from which its forms are, and must necessarily be, separated.

In quite a literal sense, aboard the USS Integrity we find commodious apartments, adrift in the cosmos. As an exploration of comics form, these commodious apartments become the inscribed frames of the multiframe adrift in the blankness of the page. As a meditation on institutional form, and the formation of the cultural techniques of discourse itself, these apartments become those of law—but relocated, no longer nestled within the ineffable corridors of Blackstone’s poky castle. Instead, they are set adrift in the abyss upon which they depend for their structural existence: a legal emblem that captures law’s foundational myth, its source code, and thereby enables its radical analysis, transcendence, or reformation.

Thus, it is with Melanie Williams that we shall mark the endpoint of this truncated discourse, and a more inspiring affirmation than Blackstone of the possibilities of a normative order that must be divided out of the continuity of the void: ‘Adrift in the cosmos ... we must build in empty space ... the greatest good that we can muster’.[161]

Acknowledgements

An early, vanishing version of this paper was presented at Graphic Justice Discussions 2019, hosted by the University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia—warm thanks to the organisers and to those in attendance who gave constructive comments. Genial thanks, also, to Penny Crofts, Tim Peters, Luca Siliquini-Cinelli, and Dominic Smith, each of whom submitted themselves to the horror of this paper in a draft form, and proffered helpful comments for its development. Recognition must go to the unnameable peer reviewers, whose kind and constructive feedback came from beyond, and also to the eminent editorial helmsmanship of Kieran Tranter. I would also like to thank Colin Reid for lending me his copy of Dawson’s Oracles of the Law. All the paper’s eventual failings, however, are of my own making.

Bibliography

Agamben, Giorgio. State of Exception. Translated by Kevin Attell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Airaksinen, Timo. The Philosophy of HP Lovecraft: The Route to Horror. New York: Peter Lang, 1999.

Augsberg, Ino. “Reading Law: On Law as a Textual Phenomenon.” Law and Literature 22, no 3 (2010): 369–393. www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/lal.2010.22.3.369

Bantinaki, Katerina. “The Paradox of Horror: Fear as a Positive Emotion.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 70, no 4 (2012): 383–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6245.2012.01530.x

Bell, John. “Sources of Law.” Cambridge Law Journal 77, no 1 (2018): 40–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008197318000053

Blandy, Sarah and David Sibley. “Law, Boundaries and the Production of Space.” Social and Legal Studies 19, no 3 (2010): 275–284. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0964663910372178

Brown, William and David H. Fleming. The Squid Cinema from Hell: Kinoteuthis Infernalis and the Emergence of Chthulhumedia. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

Bukatman, Scott. “Sculpture, Stasis, the Comics, and Hellboy.” Critical Inquiry 40, no 3 (2014): 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1086/677334

Clanchy, Michael T. From Memory to Written Record: England 1066–1307. Oxford: Blackwell, 1993.

Cotter, Joshua W. “Joshua W. Cotter” (blog). Patreon. https://www.patreon.com/joshuawcotter

———. “Joshuawcotter” (blog). Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/joshuawcotter/

———. Nod Away. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2016.

Crofts, Penny. “Monstrous Bodily Excess in The Exorcist as a Supplement to Law’s Accounts of Culpability.” Griffith Law Review 24, no 3 (2015): 372–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2015.1134036

———. “Monstrous Wickedness and the Judgment of Knight.” Griffith Law Review 21, no 1 (2012): 72–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2012.10854733

Curtis, Neal. “Doom’s Law: Spaces of Sovereignty in Marvel’s Secret Wars.” The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship 7 (2017): 9. http://doi.org/10.16995/cg.90

Dawson, John P. The Oracles of the Law. Ann Arbor: University Press of Michigan, 1968.

del Pont, Xavier M. “Confronting the Whiteness: Blankness, Loss and Visual Disintegration in Graphic Narratives.” Studies in Comics 3, no 2 (2012): 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.3.2.253_1

de Unamuno, Miguel. Tragic Sense of Life. New York: Dover Publications, 1954.

Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1974.

Dworkin, Ronald. Law’s Empire. London: Fontana Press, 1986.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1977.

Gearey, Adam. “The Parable of Bill Ayers: Comics, Allegory, and Critical Legal Thinking.” In Critical Directions in Comics Studies, edited by Thomas Giddens, 288–309. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 2020.

Giddens, Thomas. “A Series of Unfortunate Events or the Common Law.” Law and Literature (2020): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1535685X.2020.1729596

———. “Anderson v Dredd [2137] Mega-City LR 1.” International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 30, no 3 (2017): 389–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-016-9492-7

———. “Keeping up Textual Appearances: The Road Vehicles (Display of Registration Marks) Regulations 2001.” Law, Technology and Humans 2, no 1 (2020): 91–106. https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.v2i1.1402

———. “Legal Aesthetics as Visual Method.” In Routledge Handbook of Socio-Legal Theory and Methods, edited by Naomi Creutzfeldt, Marc Mason and Kirsten McConnachie, 315–328. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9780429952814/chapters/10.4324/9780429952814-23

———. “Navigating the Looking Glass: Severing the Lawyer’s Head in Arkham Asylum.” Griffith Law Review 24, no 3 (2015): 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2015.1119777

———. On Comics and Legal Aesthetics: Multimodality and the Haunted Mask of Knowing. Abingdon: Routledge, 2018.

Goodrich, Peter. Languages of Law: From Logics of Memory to Nomadic Masks. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1990.

———. “Legal Enigmas—Antonio de Nebrija, The Da Vinci Code and the Emendation of Law.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 30, no 1 (2010): 71–99. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40660431

———. Oedipus Lex: Psychoanalysis, History, Law. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

———. Reading the Law: A Critical Introduction to Legal Method and Techniques. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986.

———. “Rhetoric, Grammatology and the Hidden Injuries of Law.” Economy and Society 18, no 2 (1989): 167–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085148900000009

———. “Slow Reading.” In Nietzsche and Legal Theory: Half-Written Laws, edited by Peter Goodrich and Mariana Valverde, 185–200. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005.

———. “Specula Laws: Image, Aesthetic and Common Law.” Law and Critique 2 (1991): 233–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01128679

———. “The New Casuistry.” Critical Inquiry 33, no 4 (2007): 673–709. https://doi.org/10.1086/521565

———. “The Theatre of Emblems: On the Optical Apparatus and the Investiture of Persons.” Law, Culture and the Humanities 8, no 1 (2012): 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1743872110361226

Groensteen, Thierry. The System of Comics. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007.

Hanegraaff, Wouter J. “Fiction in the Desert of the Real: Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos.” Aries 7, no 1 (2007): 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1163/157005906X154728

Haraway, Donna. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6, no 1 (2015): 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934

Harman, Graham. Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy. Winchester: Zero Books, 2012.

Hefner, Brooks E. “Weird Investigations and Nativist Semiotics in H. P. Lovecraft and Dashiell Hammett.” Modern Fiction Studies 60, no 4 (2014): 651–676. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26421752

Hutchinson, Allan C. “Indiana Dworkin and Law’s Empire.” The Yale Law Journal 96, no 3 (1987): 637–665.

Joshi, S. T. A Dreamer and a Visionary: H P Lovecraft in His Time. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2001.

———. “Why Michel Houellebecq is Wrong about Lovecraft’s Racism.” Lovecraft Annual 12 (2018): 43–50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26868554

Kaczynski, Tom. “White Noise.” In Beta Testing the Apocalypse, 45. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2012.

Kneale, James. “From Beyond: H. P. Lovecraft and the Place of Horror.” Cultural Geographies 13, no 1 (2006): 106–126. https://doi.org/10.1191%2F1474474005eu353oa

Legendre, Pierre. God in the Mirror: A Study of the Institution of Images (Lessons III). Translated by P. G. Young. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019.

———. “Introduction to the Theory of the Image: Narcissus and the Other in the Mirror.” In Law and the Unconscious: A Legendre Reader, edited by Peter Goodrich, 211–254. London: Macmillan, 1997.

———. “The Other Dimension of Law.” In Law and the Postmodern Mind, edited by Peter Goodrich and David Gray Carlson, 175–192. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1998.

Lovecraft, H. P. “Dagon.” In The Complete Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, 25–29. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

———. “From Beyond.” In The Complete Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, 131–137. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

———. “He.” In The Complete Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, 355–364. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

———. “Herbert West—Reanimator.” In The Complete Fiction of H.P. Lovecraft, 196–222. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

———. “The Call of Cthulhu.” In The Complete Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, 381–407. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

———. “The Dunwich Horror.” In The Complete Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, 674–712. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

———. “The Horror at Red Hook.” In The Complete Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, 335–354. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

———. “The Music of Eric Zann.” In The Complete Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, 147–154. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

———. “The Tomb.” In The Complete Fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, 15–24. New York: Chartwell, 2016.

MacNeil, William P. Lex Populi: The Jurisprudence of Popular Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Martel, James. “Why Does the State Keep Coming Back? Neoliberalism, the State and the Archeon.” Law and Critique 29, no 3 (2018): 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10978-018-9234-y

Matthews, Daniel. “From Jurisdiction to Juriswriting: At the Expressive Limits of the Law.” Law, Culture and the Humanities 13, no 3 (2017): 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1743872114525745

———. “On the Law of Originary Sociability or Writing the Law.” In Being Social: Ontology, Law, Politics, edited by Tara Mulqueen and Daniel Matthews, 114–128. Oxford: Counterpress, 2015.

Moore, Alan and Jacen Burrows. Neonomicon. Rantoul: Avatar, 2011.

Pegues, Frank. “Medieval Origins of Modern Law Reporting.” Cornell Law Quarterly 38, no 4 (1953): 491–510. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol38/iss4/1/

Peters, Timothy D. and Karen Crawley, eds. Envisioning Legality: Law, Culture and Representation. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

Philippopoulos-Mihalopoulos, Andreas. “Flesh of the Law: Material Legal Metaphors.” Journal of Law and Society 43, no 1 (2016): 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2016.00740.x

———. Spatial Justice: Body, Lawscape, Atmosphere. Abingdon: Routledge, 2014.

———. “The World Without Outside.” Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities 18, no 4 (2013): 165–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2013.869018.

Salter, Mark B. “Theory of the / : The Suture and Critical Border Studies.” Geopolitics 17, no 4 (2012): 734–755. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2012.660580

Sharp, Cassandra and Marett Leiboff, eds. Cultural Legal Studies: Law’s Popular Cultures and the Metamorphosis of Law. London: Routledge, 2015.

Sharpe, Andrew N. “England’s Legal Monsters.” Law, Culture and the Humanities 5, no 1 (2009): 100–130. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1743872108096865

———. “Structured Like A Monster: Understanding Human Difference Through a Legal Category.” Law and Critique 18, no 2 (2007): 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10978-007-9013-7