|

Home

| Databases

| WorldLII

| Search

| Feedback

Law, Technology and Humans |

‘Sharing is Caring’: Copyright Metaphors and Online Sharing Norms

Kristina Chelberg

Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Abstract

Keywords: Copyright; sharing; metaphor; internet search data; Google Trends.

Because no one knows it’s illegal, and no one cares. It’s simply the language of the internet.[1]

Introduction

This article argues Australian public conceptions of the intellectual property metaphor of copyright are in flux within digital cultures of sharing. This argument emerges from the findings of a study using internet search data on online information-seeking patterns by Australians. The study is in three parts. The first part examines the competing metaphorical strategies between online copyright infringement and digital cultures of sharing, such as those promoted by social media. The second part sets out the study and the key findings of decreased information seeking for copyright-related metaphors and increased information seeking for sharing-related metaphors. The third part argues these patterns of information seeking, as a form of public mobilisation,[2] are consistent with shifting conceptions of metaphors of online copyright and sharing in contemporary Australian society.

Metaphor analysis is a valuable means to theorise the internet.[3] Conception of the internet, as a combination of both technology and practice, has historically relied on metaphor. Emergent technologies required familiar labels to navigate unfamiliar digital environments and were often ‘metaphorical loans from an analogue context’.[4] Metaphors make meaning across discourses, including the law,[5] and help conceptualise abstract concepts by bridging language, comprehension and behaviour.[6] Well-established metaphors predict both understanding and behaviour. This means metaphors both explain the social conception and direct the behavioural response consistent with that conception: ‘actions... fit the metaphor [and] in turn, reinforce the power of the metaphor’.[7] Critical metaphor analysis reveals how metaphors contribute to the interplay of social conceptions, practices and legal responses. Internet metaphors can therefore be seen to shape legal discourses at the intersection of emergent digital technologies, normative online social practices, and intellectual property law.

The key role played by metaphor in both online copyright infringement and sharing cultures has been the focus of prior research. On copyright, Loughlan found metaphors of theft in copyright piracy moralise both ‘victim’ and ‘thief’ in online copyright infringement rhetoric,[8] while Mirghani showed corporate and government anti-piracy discourse mobilised metaphors of war and terrorism to negatively frame online copyright practices and deter infringers.[9] On sharing, Larsson argued that the collaborative digital metaphors used to conceptualise the internet gave rise to ‘mismatch’ between copyright law and social norms of online behaviour.[10] Further, John analysed rising use of the word ‘share’ on social media sites to show it had evolved to ‘serve as [online] shorthand for “participate” in this site’.[11] Metaphors of copyright and sharing are in contest to conceptualise internet practices towards copyrighted material. Building on this prior work, this study argues that these ‘metaphor struggles’ are consistent with metaphorical conceptions of digital copyright and sharing undergoing a period of transition set against contemporary online practices.

This study demonstrates two key findings on Australian online-search patterns for information seeking about copyright and sharing. Visualisation of public information-seeking trends through Google Trends reveals declining information seeking for copyright together with increasing information seeking for sharing and sharing cultures. These findings are interesting because they point to an emerging potential relationship between rising ethics of online sharing norms and diminishing legitimacy of online copyright. Examination of internet-search trends for the metaphors of copyright infringement and online sharing provides insight into the rhetorical strategies of contemporary Australian copyright policy.

Competing Metaphorical Strategies

Expression of legal concepts often relies on metaphor. The word ‘copyright’ is a legal metaphorical concept of intellectual property law that describes the owner’s ‘right’ to determine who may ‘copy’ their work. Copyright discourse uses a well-established lexicon of metaphors where online copyright infringement is described as ‘piracy’ and infringers as ‘pirates’.[12] Piracy metaphors are ‘warfare’ metaphors, one of the major families of legal metaphor, and used to justify deployment of the full ‘might of the law’.[13] Warfare metaphors are expressed in rhetorical intellectual property terms of unlawfulness and conflict (such as ‘war’, ‘theft’, ‘stealing’, ‘piracy’ and ‘victims’) that frame digital sharing practices as violent and criminal.[14] For example, in April 2013, mid-way through the third season of Game of Thrones, the US Ambassador to Australia issued a warning (via Facebook) against violating copyright laws: ‘none of those reasons [are] an excuse – stealing is stealing’.[15] Copyright metaphors recruit a language of combat and criminality, a rhetorical strategy recognised by the High Court: ‘use of terms such as “piracy”, “robbery” and “theft” to stigmatise the conduct of alleged infringers of intellectual property rights, describes “the choice of rhetoric” as “significant, showing the persuasive power of proprietary concepts”’.[16]

Metaphors of copyright leverage a discourse of theft, war and deception.[17] This strategy marginalises online sharing practices as illegal—‘how can one argue for theft?’[18]—and suggests participants lack moral standards.[19] However, research shows acts of online copyright infringement may not be considered morally wrong[20] or, consistent with collaborative online sharing norms, may even contribute to the ‘greater good of society’.[21]

This leaves copyright under contest in Australia amid growing digital cultures of sharing. Contemporary online practices reveal a ‘disparity between [copyright] law and cultural use of copyrighted material’.[22] In a general sense, online sharing of copyrighted digital content on file-sharing or social media platforms without permission is an infringement of copyright, notwithstanding that content was freely available online.[23] Rates of unlawful online media consumption remain high despite educational campaigns, law-enforcement operations, reviews of Australia’s copyright regime and increased availability of legal content streaming services.[24] At the same time, social media platforms with a ‘philosophy of sharing’ promote broad sharing of digital content (such as image sharing on Instagram) irrespective of copyright status.[25] Stated motivations for infringement include, ‘it’s what everyone does’ and ‘it’s only fair’, while free and accessible online content is an expectation for a majority of Australian consumers.[26] Normative practices of online sharing are consistent with findings by Dootson and Suzor, who argue changing online behavioural norms are significant contributors to copyright infringement. They found ‘infringing behaviour is normatively acceptable’ and typified in this interview response: ‘[w]ell I think most people would class it as acceptable, even though it’s illegal ... I think it’s just become the norm’.[27] Such well-established digital practices of online media consumption[28] reflect public attitudes of indifference[29] or irrelevance[30] towards online copyright. Copyright infringement does not appear to be the objective of broad cultures of normative digital sharing; rather, motivated by participation, digital cultures are blind to legal constructs of copyright.

Normative online sharing practices are fundamental to contemporary digital cultures. John argues sharing practices are so critical to digital society that ‘ours is the age of sharing’.[31] Digital technologies, particularly social media and smartphones, have enlarged online sharing to include a wide range of social practices.[32] Online sharing practices take place across a network of cooperative platforms for participatory activities of communication, socialisation, entertainment, knowledge and research.[33] Australian internet users report ‘sharing’ to be the second most common reason for using social media.[34] As online sharing practices are adopted and repeated across the network, broad expectations of online sharing emerge as the cultural norm among internet communities.[35] Online sharing platforms encourage sharing practices that extend beyond tangible objects (files, photos, links and recommendations) to ‘fuzzy’ imperatives to share (‘share your life’, ‘share your world’ and, simply, ‘share!’).[36] The ‘ethos’ of social media is the promotion of sharing.[37] Normalisation of online sharing activities has increased user expectations, blurred the limits of online sharing practices and contributed to ‘share everything’ notions of sharing.[38] With sharing as its ‘core cultural value’,[39] sharing practices form an online ethical framework where sharing is a threshold activity to participation in digital cultures.[40] In contemporary digital society, sharing is both the act and ethic of online participation.

In a life lived in (not with) media,[41] community values associated with ‘real-life’ sharing have meaning for online sharing practices. Imbued with this ‘semantic richness’, online digital sharing metaphors carry rhetorical force to influence online behaviour.[42] Online platforms draw on powerful connotations of sharing as a social good to engage and activate users.[43] Indeed, Facebook leveraged the ‘warm glow’ around sharing when it positioned the values of sharing at its core. Mark Zuckerberg characterised sharing as one of Facebook’s fundamental activities: ‘When share more, the world becomes more open and connected’.[44]

Sharing metaphors encourage user participation in online sharing practices and reinforce cooperative behavioural norms by association with positive social values. The metaphor ‘sharing is caring’ explicitly expresses this online sharing ethic to press participation in online cultures, and, at the same time, designates not sharing as ‘uncaring’. Therefore, metaphors of sharing both aid conception (what can be done online) and direct behaviour (what should be done online), in turn, reinforcing the imperative to share. In digital communities where sharing is the ‘constitutive act of being online’,[45] users are expected to share with their (online) contacts and (social media) friends. The ethics of sharing in a digital society mean that ‘good subjects post, update, like, tweet, retweet, and most importantly, share’.[46] Sharing metaphors such as ‘like’, ‘friend’, ‘community’ and ‘social network’ promote online practices that prioritise participation in digital cultures. Digital cultures have shaped both the language and conception of online sharing—from early literal ‘time-sharing’ of computers, through ‘disk-sharing’ and ‘file-sharing’, to broad notions of contemporary ‘sharing’ of digital content and personal information online.[47]

Competing metaphors of copyright and sharing signify tension between intellectual property rights and online sharing practices in a contemporary digital society. Through their respective metaphors, the contest between online ‘piracy’ and ‘sharing’ is made explicit:

It seems that sharing, like stealing, has entered the language of digital cultures due to mere ideological reasons. Both terms are used to justify new forms of social practices morally. Sharing is good, stealing is bad. But copying is neither good nor bad. Copying is neither sharing nor stealing, it is just copying, multiplying.[48]

Warfare-based copyright metaphors frame online participatory practices as criminal and pirates as enemies of creativity.[49] In contrast, sharing metaphors advance the ‘culture’ and ‘good’ of sharing, where sharing is the primary act of online participation.[50] Identification of the ‘metaphor struggles’ between copyright and sharing provides a lens through which to examine public conceptions of online copyright infringement against normalised online sharing practices.

Study and Key Findings

This article uses the digital methodology of internet search data (Google Trends) to examine the ‘metaphor struggles’ between online copyright infringement and digital sharing cultures. Internet methods are used to explore information-seeking patterns for key metaphors of copyright and sharing and are shown to be an interesting approach to consider shifting Australian conceptions of online copyright.[51]

Internet search data is a growing digital methodology anticipated to have valuable application in the areas of policy and law.[52] Internet search data records the search terms entered into internet search engines to reveal the information-seeking behaviours of people for facts, places, people and topics.[53] Google publishes its internet search data through Google Trends.[54] Internet search data has been used to study a wide range of humanities and social sciences topics,[55] including law, with emerging research using it to explore online copyright infringement.[56] Studies have demonstrated a correlation between internet search data and social behaviours or attitudes, including public attention,[57] public interest[58] and changes in economic and social perceptions.[59] Internet search data records cumulative online information-seeking activity by population (specific to topic, time and location) and, in this sense, represents a ‘form of societal mobilisation’.[60]

Conventional research on online copyright infringement research has relied on self-reporting by survey participants about their online copyright practices.[61] Yet, survey data has limitations for online copyright research.[62] Critically, survey participants tend to underreport illegal or sensitive behaviour (known as social desirability bias).[63] Copyright infringement survey participants are less likely to self-report infringing behaviour to avoid penalty and because infringement is known to be technically (if not normatively) wrong.[64]

Internet search data offers advantages for online copyright research. The availability of anonymous online information-seeking data has particular application to investigate behaviour sensitive to social desirability bias where the internet itself facilitates the behaviour in question, namely, online copyright infringement.[65] Further, search engines are known to operate as ‘gateways’ to online copyright infringement, particularly for first-time users of unauthorised content sources.[66] Internet search methods thus present an alternative ‘infoveillance’ approach to study online copyright practices. In recording one of the primary activities of contemporary human life—searching for information online—internet search methods hold potential for socio-legal research.[67] Internet search data complements traditional data collection methods because it discloses uncensored information-seeking behaviours[68] and represents a form of public mobilisation on topics of social interest.[69]

Method to Visualise Metaphor Patterns

This section describes the method used to map internet-search trends for key metaphors of copyright and sharing to visualise potential changes in conceptions of copyright, an approach adapted from a methodology shown to map changes in social attitudes.[70] The method uses a multi-step process to generate a Google Trends Search Query Index (SQI) for ‘metaphor clusters’[71] related to copyright and sharing. The generated SQI is a visual representation of public information-seeking patterns for each metaphor cluster.

As a first step, three words or phrases were selected to represent a metaphor cluster from dominant and recurring themes in the academic, media and public discourse on online copyright infringement and digital sharing practices. For each metaphor cluster, words were chosen based on their strength to act as ‘shorthand’ within the discourse.[72] The selected words are central metaphors that signify cultural norms about online copyright and sharing practices. The words ‘copyright law’, ‘copyright piracy’ and ‘war on copyright’ were selected to represent the copyright or piracy metaphor cluster. These key piracy phrases are based on warfare metaphors that scaffold a ‘rhetorical construction of [copyright infringement] as criminal’.[73] The words ‘sharing economy’, ‘sharing culture’ and ‘sharing is caring’ were selected to represent the sharing metaphor cluster. The phrase ‘sharing is caring’ is a key slogan of the sharing discourse, as it is the ‘warm glow around sharing’ that promotes ‘sharing with the people we care about’.[74] As a metaphor, ‘sharing is caring’ leverages strong semantic association with the social good to endorse online sharing norms. Further, by activating these associations, the phrase is observed to ‘push back against the criminalisation of culture’.[75]

Explicit limits are acknowledged with the phrases selected for each metaphor cluster. The metaphor terms in each cluster were chosen based on their prevalence in the respective discourses on copyright and sharing; it follows that selection of a different set of terms would give rise to different findings. It is not the aim nor claim of this study the selected terms will capture all internet search interest on the topics of piracy or sharing. In addition, due to the broad or multiple meanings of some terms, both metaphor cluster SQIs may include unrelated results. It is also true that only a proportion of ‘sharing’ searches are related to information seeking about sharing copyright material, while ‘copyright’ searches will capture general interest and legal research searches, as well as information seeking about how to access copyright material. However, these visualised findings are interesting, not for the volume of searches, but for the shifting patterns of public information seeking for metaphors related to owning and sharing within digital cultures.

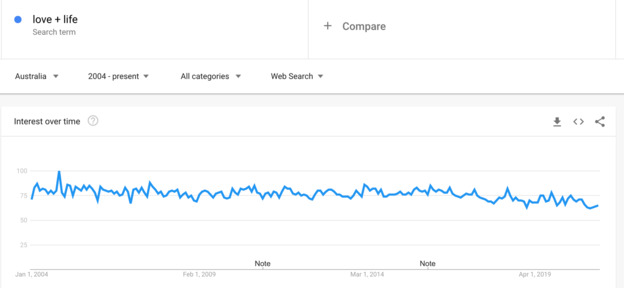

Information-seeking trends for each metaphor cluster were then visualised with a series of SQIs to show relative internet search interest over a 17-year period from 2004 to 2021.[76] The SQIs for each metaphor cluster were generated by inputting the words as a combined search into Google Trends using settings for Australian web searches since 2004.[77] Screenshots of the SQIs were taken of the Google Trends website and are shown in Figures 1 to 4. The SQI findings were noted against relevant events (e.g., legislative changes or technology releases) representing key developments in copyright law and online sharing practices. A comparative SQI over the period 2004 to 2021 was generated to show relative changes in search trends for piracy and sharing metaphors. By way of reference, a SQI for unrelated benchmark terms, ‘love’ and ‘life’,[78] is shown first in Figure 1 as an indicator of stable general internet search volume over the same period.

Figure 1: Combined Benchmark Search Query Index for ‘love + life’ (31 March 2021) Data source: Google Trends (https://www.google.com/trends)

The SQI for combined search terms ‘love + life’ displays stable search interest between January 2004 (71) and January 2021 (63). The Benchmark SQI acts as a useful comparator for visualising changing patterns in public information-seeking interest for piracy and sharing search terms over time.

Metaphor Pattern Findings

The Search Query Indexes for the piracy and sharing metaphor clusters are set out in Figures 2 to 5.

Piracy Search Query Index

Figure 2: Combined piracy metaphors Search Query Index for ‘copyright law + copyright piracy + war on copyright’ (31 March 2021) Data source: Google Trends (https://www.google.com/trends)

The SQI for the combined words of the piracy metaphor cluster commences in January 2004 at 100, rises and falls sharply until March 2006, then adopts an overall downward trend characterised by small fluctuations,[79] falling below 25 in 2010 and decreasing to 3 in January 2021. Relevant Australian events over this period include the extension of the copyright term to life of author plus 70 years (2005), Australian Law Reform Commission recommendation for ‘fair use’ (2013),[80] introduction of ‘site-blocking’ powers for ‘pirate’ websites (2015), first application by Federal Court of site-blocking powers (2016)[81] and government review into modernisation of Australian copyright laws (2018).[82] These events are noted to background developments in Australian copyright law and policy, and while not suggested to be causative of information seeking for copyright, they may have contributed to shifting patterns of public interest. The SQI for piracy metaphor cluster visualises declining search trends for key piracy metaphors and is consistent with fewer numbers of Australian internet users seeking information associated with copyright infringement.

Figure 3: Combined sharing metaphor Search Query Index for ‘sharing is caring + sharing culture + sharing economy’ (31 March 2021) Data source: Google Trends (https://www.google.com/trends)

The SQI for the combined words of the sharing metaphor cluster begins in January 2004 at 0, exhibiting a large spike in September 2004 (100), with peaks again between March 2006 (24) and May 2008 (27), fluctuating between 2008 and 2012, and thereafter displaying a gradual overall upward trend, passing 25 in March 2015, reaching a high of 39 in May 2018, before ending on 5 in February 2021. Relevant Australian events over this period relating to the rise of digital sharing cultures include the launch of Facebook (2005), release of the iPhone (2009), high rates (66%) of smart phone ownership (2016),[83] widespread (79%) adoption of social media (2017) and daily use (79%) of social media (2020).[84] The SQI for the sharing metaphor clusters visualises increasing search trends for key sharing metaphors and is consistent with greater numbers of Australian internet users seeking online information on the topic of sharing and sharing cultures.

The overall downward trend for piracy metaphors and upward trend for the sharing metaphors is demonstrated in the Comparative SQI in Figure 4, which displays the combined words of the piracy (blue) against the sharing (red) metaphor clusters.

Figure 4: Comparative Search Query Index for piracy (blue) and sharing (red) (31 March 2021) Data source: Google Trends (https://www.google.com/trends)

The Comparative SQI commences in January 2004, showing piracy (blue) search interest at the maximum over sharing (red) (100:0), with piracy terms tracking steeply downwards against a gradual climb in sharing terms through January 2010 (11:0), January 2016 (7:4) and January 2020 (4:1) to reach similar search volumes in January 2021 (3:2).

The series of SQIs visualise shifting Australian patterns of information seeking for metaphor clusters relating to online copyright infringement and sharing cultures. The findings show a trend towards fewer searches using key piracy metaphors and greater searches using key sharing metaphors. A linear trendline view of the Comparative SQI showing relative public search interest for copyright and sharing is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Search Interest Trendline for piracy (blue) vs sharing (red) metaphor clusters from 2004 to 2022 (forecast) Data source: Google Trends (https://www.google.com/trends)

Plotting annual relative search interest for each topic, Figure 5 visualises a decreasing volume of public information seeking for copyright metaphors set against increasing volume of public information seeking for sharing metaphors. As a form of public mobilisation, these findings offer interesting insight into the ‘metaphorical struggles’ between key metaphors of copyright and sharing. Visualised metaphor internet search patterns are consistent with trends identified in empirical findings of traditional surveys on online copyright infringement as well as internet activity and social media practices,[85] and have relevance for conceptions of owning and sharing in a digital age.

This study has used internet search data to visually demonstrate two key findings about Australian patterns of online-search interest for topics of copyright and sharing. The first finding shows declining information seeking for copyright-related topics, while the second finding shows increasing information seeking for sharing-related topics. Diminishing public online-search interest for copyright is consistent with both empirical findings from traditional surveys on copyright infringement and prior research by Dootson and Suzor that copyright may be losing its normative legitimacy.[86] This finding also raises questions about the reduced normative value of copyright piracy metaphors as a strategy to influence contemporary digital activities. The second finding demonstrates that, over the same period, increasing public online-search interest for sharing and sharing cultures is consistent with research that sharing is a fundamental activity of digital participation[87] and is also reflective of enlarged influence of sharing metaphors in online communities facilitated by social media.

Mapped together using Google Trends over 17 years visualises an opposite trendline between public patterns of information seeking for metaphors of copyright (decreasing) against information seeking for metaphors of sharing (increasing). Arising as an interpretation of the primary findings, this raises a potential association between observed patterns of information seeking for topics of copyright and sharing. While the findings do not support evidence of a true causal relationship, the negative correlation visualises a potential interconnection between rising ethics of online sharing practices and declining social legitimacy of online copyright amid contemporary digital cultures of sharing. While this potential relationship is observed due to the terms selected for binary comparison, it discloses an interesting question for further investigation.

The limits of this study are acknowledged. As a developing methodology, internet search data findings are exploratory rather than conclusive.[88] Limitations of internet search data include lack of information on user motivation,[89] changes in search terms over time and representation of the wider population.[90] The author recognises that the low volume of searches for the queried search terms reflects the fact that copyright and sharing are not high-volume, popular search topics in Australia,[91] and nor does online-search interest equate to a measure of public salience.[92] Therefore, although findings are treated with caution and triangulated with traditional datasets,[93] visualised information-seeking patterns represent a valuable approach to identify broader trends in public interest.[94]

Shifting Conceptions of Copyright

This article focused on metaphors in online copyright infringement and sharing practices. Making explicit the strategic role of metaphor is important because the efficacy of copyright law relies not only on legal sanction[95] but also upon public conceptions of copyright—conceptions that are constructed by metaphors. Online metaphors are the ‘engineering’ words used to fill the language and conceptual void created by emergent technologies; the ‘mental models’ relied on by internet users to label and navigate digital landscapes. Legal and social metaphors both explain and predict behaviour, thereby reinforcing their imperative power. However, metaphor struggles occur when ‘approved’ metaphorical concepts are in transition, ‘shaped by conditions that once prevailed, but do so no longer’.[96] Shifting social norms are, therefore, revealed in the evolution of metaphorical concepts and provide a mechanism to examine interactions between language and the law.[97] Levi identified a cyclical process for legal concepts: from creation, where words are ‘tried out’; through a period where the concept is ‘more or less fixed’; and, finally, where the concept breaks down because the ‘suggestive influence of the word is no longer desired’:

... in speaking of metaphors, the word starts out to free thought and ends by enslaving it. The movement of concepts into and out of the law makes the point. If the society has begun to see certain significant similarities or differences, the comparison emerges with a word. When the word is finally accepted, it becomes a legal concept. Its meaning continues to change... The words change to receive the content which the community gives to them.[98]

Contests in legal and social concepts are, therefore, voiced in contests between metaphors. Just as competing metaphors signify competing values,[99] tensions between metaphors of copyright and sharing are consistent with the contested status of online copyright. Therefore, disputes between metaphors of the copyright and sharing discourses provide insight into disputed online copyright and sharing practices in contemporary digital cultures.

This study has demonstrated trends toward decreasing internet searches for key copyright metaphors and, over the same period, increasing internet searches for key sharing metaphors, raising a potential relationship between these trends. The trends identified are consistent with fundamental tensions between restrictive online copyright infringement laws and expansive sharing practices of digital cultures.[100] The study’s findings visualise shifting patterns of public information seeking consistent with the metaphorical conceptions of digital copyright and sharing undergoing a period of transition. The conceptual transition of copyright is consistent with continued high rates of online copyright infringement[101] and observations that the cultural construct of copyright may be losing its normative legitimacy.[102] At the same time, widespread participation in broad online sharing practices is promoted through digital conceptions of online sharing as a social good.[103] At the intersection of shifting conceptions, ‘metaphor struggles’ reveal how ‘technology, ... law and the social realm grind their understandings around particularly challenging events’.[104] Copyright, as a metaphor of intellectual property, may be in transition through the ‘break-down’ stage of the metaphor cycle.[105] These findings raise questions for the continued rhetorical strategy of piracy, where copyright’s legitimacy is disputed by rising cultures of online sharing.[106] These patterns of information seeking, as a form of public mobilisation, can be understood in terms of disparity between conceptions of copyright piracy and digital sharing practices, and cast doubt over the ongoing effectiveness of piracy metaphors to guide social behaviour. Acknowledgement of these shifting metaphorical conceptions of copyright and sharing is relevant because ‘legal frameworks that support them [copyright] are not intrinsic truth but cultural constructs building from competing social demands. Laws are seldom fixed and absolute, but simply reflect the current state of any cultural contest’.[107]

Critical analysis of legal and social metaphors provides a framework to deconstruct their normative influence in contemporary online activities. Metaphors are integral to constructions of emerging and abstract technologies where public conceptions and legal responses are limited by the legitimacy of the chosen metaphor.[108] Metaphors in legal discourse are signifiers of the conceptual ‘right’,[109] but their rhetorical influence is continually subject to shifting public conceptions and practices. As online copyright is contested by contemporary digital cultures, Google Trends’ visualisation of shifting patterns of public information seeking for metaphors of copyright and sharing is consistent with changing Australian conceptions of online copyright, access and ownership.

Conclusion

Acknowledging the limits of traditional copyright survey methods, this study adopted an exploratory methodology to investigate the utility of internet search data for online copyright research. Internet search data (Google Trends) is well-suited to study social problems, such as online copyright infringement, facilitated by the internet and affected by social desirability bias. The findings visualised changing patterns of metaphor usage consistent with widely observed patterns in contemporary online copyright and sharing practices. This paper contributes a clearer understanding of the role of metaphors in contested online practices of copyright infringement and digital sharing norms—the ‘copyright wars’ against ‘sharing is caring’.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the guidance of Associate Professor Jane Johnston, The University of Queensland, with the concept for this work, as well as the encouragement of Professor Kieran Tranter, Queensland University of Technology, in the development of this paper. Your generosity of both time and support is appreciated.

Bibliography

ALRC. Copyright and the Digital Economy: Final Report. Sydney: The Commission, 2013.

Anderson, Ashton, Sharad Goel, Gregory Huber, Neil Malhotra and Duncan J. Watts. “Political Ideology and Racial Preferences in Online Dating.” Sociological Science; Stanford 1 (February 2014): 28–40. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/10.15195/v1.a3

Askitas, Nikolaos and Klaus F. Zimmermann. “The Internet as a Data Source for Advancement in Social Sciences.” International Journal of Manpower 36, no 1 (March 17, 2015): 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-02-2015-0029

Australian Copyright Council (ACC). “Internet: Copying and Downloading - ACC - INFO056 - Australian Copyright Council,” 2015. https://www.copyright.org.au/browse/book/ACC-Internet:-Copying-and-Downloading-INFO056

Baram-Tsabari, Ayelet, Elad Segev and Aviv J. Sharon. “What’s New? The Applications of Data Mining and Big Data in the Social Sciences.” In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods, edited by Nigel G. Fielding, Raymond M. Lee and Grant Blank, 92–106. 55 London: SAGE, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957992

Belk, Russell. “You Are What You Can Access: Sharing and Collaborative Consumption Online.” Journal of Business Research 67, no 8 (2014): 1595–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001

Bosher, Hayleigh and Sevil Yeşiloğlu. “An Analysis of the Fundamental Tensions between Copyright and Social Media: The Legal Implications of Sharing Images on Instagram.” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology 33, no 2 (2019): 164–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2018.1475897

Castells, Manuel. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=472226

Cohen, I. Glenn and Jonathan H. Blavin. “The Evolution of Internet Metaphors in Law and Commentary.” Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 16, no 1 (2003): 265–285.

Corte, Charlotte Emily De and Patrick Van Kenhove. “One Sail Fits All? A Psychographic Segmentation of Digital Pirates.” Journal of Business Ethics 143, no 3 (2017): 441–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2789-8

Coyle, James R., Stephen J. Gould, Pola Gupta and Reetika Gupta. “‘To Buy or to Pirate’: The Matrix of Music Consumers’ Acquisition-Mode Decision-Making.” Journal of Business Research, Impact of Culture on Marketing Strategy, 62, no 10 (2009): 1031–1037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.002

Danaher, Brett, Michael D. Smith, Rahul Telang and Siwen Chen. “The Effect of Graduated Response Anti-Piracy Laws on Music Sales: Evidence from an Event Study in France.” The Journal of Industrial Economics 62, no 3 (2014): 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/joie.12056

Department of Communications & Arts (Cth). Consumer Survey on Online Copyright Infringement 2018. Department of Communications & Arts (Cth), 2018. https://www.communications.gov.au/departmental-news/new-online-copyright-research-released-2018

Department of Infrastructure, Transport. “2020 Consumer Copyright Infringement Survey.” Text. Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, April 6, 2021. https://www.communications.gov.au/documents/2020-consumer-copyright-infringement-survey

———. “Copyright Modernisation Consultation.” Text. Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, May 25, 2018. https://www.communications.gov.au/have-your-say/copyright-modernisation-consultation

Deuze, Mark. Media Life. Cambridge: Polity, 2012.

Dilmperi, Athina, Tamira King and Charles Dennis. “Toward a Framework for Identifying Attitudes and Intentions to Music Acquisition from Legal and Illegal Channels.” Psychology & Marketing 34, no 4 (2017): 428–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20998

Dootson, Paula and Nicolas Suzor. “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax: Divergent Views about Copyright Business Models and the Willingness of Australian Consumers to Infringe.” University of New South Wales Law Journal 38, no 1 (2015): 206–239.

Facebook. “Facebook Redesigns Privacy.” The Facebook Blog (blog). May 26, 2010. https://about.fb.com/news/2010/05/facebook-redesigns-privacy/

Funk, Stephan M. and Daniela Rusowsky. “The Importance of Cultural Knowledge and Scale for Analysing Internet Search Data as a Proxy for Public Interest toward the Environment.” Biodiversity and Conservation 23, no 12 (2014): 3101–3112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-014-0767-6

Groves, Robert M. “Three Eras of Survey Research.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75, no 5 (2011): 861–871. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr057

Hardy, Wojciech. “Pre-Release Leaks as One-Time Incentives for Switching to Unauthorised Sources of Cultural Content.” In IBS Working Paper, Vol. 03/2018, 2018. http://ibs.org.pl/app/uploads/2018/04/IBS_Working_Paper_03_2018.pdf

Herman, Bill D. “Breaking and Entering My Own Computer: The Contest of Copyright Metaphors.” Communication Law and Policy 13, no 2 (2008): 231–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/10811680801941276

Ilic, Dan. “Fair Use and the Right to Be Stupid.” In Copyfight, edited by Phillipa McGuinness, 169–173. Sydney: NewSouth, 2015.

John, Nicholas A. “File Sharing and the History of Computing: Or, Why File Sharing Is Called ‘File Sharing.’” Critical Studies in Media Communication 31, no 3 (2014): 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2013.824597

———. “Sharing and Web 2.0: The Emergence of a Keyword.” New Media & Society 15, no 2 (2013): 167–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812450684

———. The Age of Sharing. Cambridge: Polity, 2017.

Johnstone, Megan-Jane. “Metaphors, Stigma and the ‘Alzheimerization’ of the Euthanasia Debate.” Dementia 12, no 4 (2013): 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211429168

Jun, Seung-Pyo, Hyoung Sun Yoo and San Choi. “Ten Years of Research Change Using Google Trends: From the Perspective of Big Data Utilizations and Applications.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 130 (2018): 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.11.009

Kaminski, Marcin De, Måns Svensson, Stefan Larsson, Johanna Alkan Olsson and Kari Ronkko. “Studying Norms and Social Change in a Digital Age: Identifying and Understanding a Multidimensional Gap Problem.” In Social and Legal Norms: Towards a Socio-Legal Understanding of Normativity (1st ed.), edited by Matthias Baier. Routledge, 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315609416

Karpińska, Patrycja. “The Internet in the Mind: The Conceptualisation of the Category of the Internet in English.” E-Methodology 2016, no 3 (2016): 9–17.

Kennedy, Jenny. “Rhetorics of Sharing: Data, Imagination and Desire.” In Unlike Us Reader: Social Media Monopolies and Their Alternatives, edited by Geert Lovink and Miriam Rasch, 127–136. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2013.

———. “Sharing in Networked Culture: Imagination, Labour and Desire.” PhD, Swinburne University, 2014.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Larsson, Stefan. Conceptions in the Code: How Metaphors Explain Legal Challenges in Digital Times. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

———. “Conceptions in the Code: What ‘The Copyright Wars’ Tell Us about Creativity, Social Change and Normative Conflicts in the Digital Society.” Societal Studies 4, no 3 (2012): 1009–1030.

Larsson, Stefan, Susan Wnukowska‐Mtonga, Måns Svensson and Marcin De Kaminski. “Parallel Norms: File-Sharing and Contemporary Copyright Development in Australia.” The Journal of World Intellectual Property 17, no 1–2 (2014): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwip.12018

Leaver, Tama. “Balancing Privacy: Sharenting, Intimate Surveillance and the Right to Be Forgotten.” MediArXiv, May 29, 2020. https://doi.org/10.33767/osf.io/fwmr2

Leeuw, H.B.M. “Using Big Data to Study Digital Piracy and the Copyright Alert System.” In Cyber Society, Big Data, and Evaluation: Comparative Policy Evaluation (1st ed.), edited by Gustav Jakob Petersson and Jonathan D. Breul. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Levi, Edward Hirsch. “An Introduction to Legal Reasoning.” The University of Chicago Law Review 15, no 3 (1948): 501–574.

Loughlan, Patricia. “Pirates, Parasites, Reapers, Sowers, Fruits, Foxes... The Metaphors of Intellectual Property.” Sydney Law Review 28, no 2 (June 2006): 211–226.

———. “‘You Wouldn’t Steal a Car...’: Intellectual Property and the Language of Theft.” European Intellectual Property Review 29, no 10 (October 2007): 401–405.

Lunceford, Brett and Shane Lunceford. “Meh. The Irrelevance of Copyright in the Public Mind.” Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property 7, no 1 (2008): 33–49.

MacNeill, Kate. “Torrenting Game of Thrones: So Wrong and yet so Right.” Convergence 23, no 5 (2017): 545–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856516640713

Malcevschi, Sergio, Agnese Marchini, Dario Savini and Tullio Facchinetti. “Opportunities for Web-Based Indicators in Environmental Sciences.” PLOS ONE 7, no 8 (2012): e42128. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042128

Matsa, Katerina Eva, Amy Mitchell and Galen Stocking. “Searching for News: The Flint Water Crisis (Methodology).” Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project (blog). April 27, 2017. http://www.journalism.org/2017/04/27/google-flint-methodology/

Mellon, Jonathan. “Internet Search Data and Issue Salience: The Properties of Google Trends as a Measure of Issue Salience.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 24, no 1 (2014): 45–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2013.846346

Mirghani, Suzannah. “The War on Piracy: Analyzing the Discursive Battles of Corporate and Government-Sponsored Anti-Piracy Media Campaigns.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 28, no 2 (2011): 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2010.514933

Nghiem, Le T. P., Sarah K. Papworth, Felix K. S. Lim and Luis R. Carrasco. “Analysis of the Capacity of Google Trends to Measure Interest in Conservation Topics and the Role of Online News.” PLoS ONE 11, no 3 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152802

Nuti, Sudhakar V., Brian Wayda, Isuru Ranasinghe, Sisi Wang, Rachel P. Dreyer, Serene I. Chen and Karthik Murugiah. “The Use of Google Trends in Health Care Research: A Systematic Review.” Edited by Martin Voracek. PLoS ONE 9, no 10 (2014): e109583. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109583

Osenga, Kristen. “The Internet is Not a Super Highway: Using Metaphors to Communicate Information and Communications Policy.” Journal of Information Policy 3 (2013): 30–54. https://doi.org/10.5325/jinfopoli.3.2013.0030

Phau, Ian, Min Teah and Michael Lwin. “Pirating Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of Cyberspace.” Journal of Marketing Management 30, no 3–4 (2014): 312–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.811280

Reyes, Tomas, Nicolas Majluf and Ricardo Ibanez. “Using Internet Search Data to Measure Changes in Social Perceptions: A Methodology and an Application.” Social Science Quarterly 99, no 2 (2018): 829–845.

Richard, Isabelle. “Metaphors in English for Law: Let Us Keep Them!” Lexis. Journal in English Lexicology, no 8 (2014). https://doi.org/10.4000/lexis.251

Ripberger, Joseph T. “Capturing Curiosity: Using Internet Search Trends to Measure Public Attentiveness.” Policy Studies Journal 39, no 2 (2011): 239–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00406.x

Sensis. Sensis Social Media Report 2017, Chapter 1 - Australians and Social Media, 2017. https://www.sensis.com.au.

———. Yellow Social Media Report 2020 - Consumers. Melbourne, 2020. https://www.yellow.com.au/social-media-report/

Stalder, Felix and Wolfgang Sützl. “Ethics of Sharing.” International Review of Information Ethics 15 (2011). https://doi.org/10.29173/irie225

Statista. “Google Market Share Countries 2019.” Statista. Accessed June 25, 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/220534/googles-share-of-search-market-in-selected-countries/

———. “Search Engine Market Share Worldwide 2019.” Statista. Accessed June 25, 2019. https://www.statista.com/statistics/216573/worldwide-market-share-of-search-engines/

Steinberg, Stacey B. “Sharenting: Children’s Privacy in the Age of Social Media.” Emory Law Journal 66 (2017).

Stephens-Davidowitz, Seth. Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us about Who We Really Are (1st ed.). New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Suzor, Nicolas. “Free-Riding, Cooperation, and Peaceful Revolutions in Copyright.” Harvard Journal of Law & Technology 28, no 1 (2014): 137–194.

Tay Wee Teck, Joseph and Mark McCann. “Tracking Internet Interest in Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids Using Google Trends.” International Journal of Drug Policy 51 (2018): 52–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.11.001

Tourangeau, Roger and Ting Yan. “Sensitive Questions in Surveys.” Psychological Bulletin 133, no 5 (2007): 859–883. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859

Turkle, Sherry. “Connected, but Alone?” TED, February 2012. https://www.ted.com/talks/sherry_turkle_alone_together

Vaidhyanathan, Siva. Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How It Threatens Creativity. New York, NY: NYU Press, 2001. http://muse.jhu.edu/book/7525.

Van der Sar, Ernesto. “Who’s Pirating Game of Thrones, and Why?” TorrentFreak (blog). May 20, 2012. https://torrentfreak.com/whos-pirating-game-of-thrones-and-why-120520/

Whyte, Christopher E. “Thinking Inside the (Black) Box: Agenda Setting, Information Seeking, and the Marketplace of Ideas in the 2012 Presidential Election.” New Media & Society 18, no 8 (2016): 1680–1697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814567985

Wittel, Andreas. “Qualities of Sharing and Their Transformations in the Digital Age.” International Review of Information Ethics 15, no 9 (2011): 3–8.

Young, Sherman. “A Hack for the Encouragement of Learning.” In Copyfight, edited by Phillipa McGuinness, 35–48. Sydney: NewSouth, 2015.

Primary Legal Materials

Network Ten Pty Limited v TCN Channel Nine Pty Limited [2004] HCA 14 (High Court of Australia 2004).

Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2016] FCA 1503, FCA 1503 (Federal Court of Australia 2016).

[1] Ilic, “Fair Use and the Right to Be Stupid,” 172.

[2] Whyte, “Thinking inside the (Black) Box.”

[3] Castells, Communication Power, 126; John, “File Sharing and the History of Computing,” 198; Karpińska, “The Internet in the Mind,” 9; Osenga, “The Internet Is Not a Super Highway,” 30; Herman, “Breaking and Entering My Own Computer,” 241.

[4] For example, a computer interface is represented by visual metaphors, such as ‘desktop’, ‘files in folders’ and ‘trash’, while the metaphors of ‘cyberspace’, ‘information superhighway’, ‘network society’, ‘search engine’ and ‘cloud’ were used to describe the internet: Larsson, “Conceptions in the Code,” 1011.

[5] Loughlan, “Pirates, Parasites, Reapers, Sowers, Fruits, Foxes,” 214; Herman, “Breaking and Entering My Own Computer,” 234.

[6] Seminal metaphor scholars Lakoff and Johnson argue, ‘Metaphor is pervasive in everyday life, not just in language but in thought and action. Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is fundamentally metaphorical in nature. ... Our concepts structure what we perceive, how we get around in the world, and how we relate to other people. Our [metaphorical] conceptual system thus plays a central role in defining our everyday realities ... [so] then the way we think, what we experience, and what we do every day is very much a matter of metaphor’: Lakoff, Metaphors We Live By, 3.

[7] Lakoff, Metaphors We Live By, 156.

[8] Loughlan, “‘You Wouldn’t Steal a Car...’.”

[9] Mirghani, “The War on Piracy.”

[10] Larsson, “Conceptions in the Code,” 1025. Terms such as ‘the network society’ and the ‘social network’ are metaphors that emphasise the societal qualities of the internet: Larsson, “Conceptions in the Code,” 1014.

[11] John, “Sharing and Web 2.0,” 174.

[12] Loughlan, “Pirates, Parasites, Reapers, Sowers, Fruits, Foxes.”

[13] Richard, “Metaphors in English for Law,” 107, 108.

[14] Whether copyright infringement can be technically equated with theft of physical property is another question of law, as examined by Herman, “Breaking and Entering My Own Computer,” 244; Loughlan, “‘You Wouldn’t Steal a Car...’,” 402.

[15] MacNeill, “Torrenting Game of Thrones,” 545. Australia gained notoriety as a world leader in illegal downloading of entertainment goods for file-sharing of the HBO television series, Game of Thrones. See Van der Sar, “Who’s Pirating Game of Thrones, and Why?”

[16] Network Ten Pty Limited v TCN Channel Nine Pty Limited [2004] HCA 14.

[17] Mirghani, “The War on Piracy,” 116, 117; Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax,” 223. Similarly, Johnstone argues the term ‘piracy’ exploits its criminal connotations, to amplify its communicative power and ‘lend legitimacy and even urgency’ to the discourse: Johnstone, “Metaphors, Stigma and the ‘Alzheimerization’ of the Euthanasia Debate,” 384.

[18] Vaidhyanathan, Copyrights and Copywrongs, 12.

[19] MacNeill, “Torrenting Game of Thrones,” 548; Corte, “One Sail Fits All?,” 455.

[20] Suzor, “Free-Riding, Cooperation, and Peaceful Revolutions in Copyright”; Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax.”

[21] Phau, “Pirating Pirates of the Caribbean,” 325.

[22] Bosher, “An Analysis of the Fundamental Tensions between Copyright and Social Media,” 181.

[23] Australian Copyright Council (ACC), “Internet: Copying and Downloading - ACC - INFO056 - Australian Copyright Council.” Note the focus of this article is on public attitudes toward online copyright amid contemporary digital cultures, rather than legal technicalities of online copyright infringement.

[24] Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax,” 206; Larsson, “Parallel Norms,” 11; Department of Infrastructure, “2020 Consumer Copyright Infringement Survey,” 3. The 2020 report is sixth in a series of annual government survey into patterns of infringement of online media content. While the series finds declining general trends in unlawful consumption of online media content (music, video games, movies, live sport and TV), the overall rates of unlawful consumption remain significant at 34% of consumers.

[25] Bosher, “An Analysis of the Fundamental Tensions between Copyright and Social Media,” 165.

[26] Department of Communications & Arts (Cth), Consumer Survey on Online Copyright Infringement 2018, 66, 68.

[27] Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax,” 233.

[28] Department of Infrastructure, “2020 Consumer Copyright Infringement Survey.”

[29] Lunceford, “Meh. The Irrelevance of Copyright in the Public Mind,” 33.

[30] Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax.” Suzor, “Free-Riding, Cooperation, and Peaceful Revolutions in Copyright.”

[31] John, The Age of Sharing, 5; John, “Sharing and Web 2.0,” 178.

[32] John, The Age of Sharing, 5; Wittel, “Qualities of Sharing and Their Transformations in the Digital Age,” 3.

[33] Well-known examples of sharing platforms relying on cooperative practices of sharing digital content within an online community include Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, Spotify, Wikipedia and ResearchGate.

[34] Sensis, Yellow Social Media Report 2020 - Consumers, 16.

[35] Phau, “Pirating Pirates of the Caribbean,” 325; Belk, “You Are What You Can Access,” 1595.

[36] John, “Sharing and Web 2.0,” 175.

[37] Bosher, “An Analysis of the Fundamental Tensions between Copyright and Social Media,” 164.

[38] John, “Sharing and Web 2.0,” 173; Wittel, “Qualities of Sharing and Their Transformations in the Digital Age,” 6. One example of the reach of broad online sharing norms is ‘sharenting’, where parents (are expected to) share personal images and videos of their young children online, a normalised parenting practice in the era of social media: Steinberg, “Sharenting”; Leaver, “Balancing Privacy”.

[39] Stalder, “Ethics of Sharing,” 2. Castells foreshadowed the significance of contemporary sharing: ‘the protocols of communication are not based on the sharing of culture, but on the culture of sharing’ (Communication Power, 167), while Turkle put it simply, ‘I share therefore I am’ (“Connected, but Alone?”).

[40] John, “Sharing and Web 2.0,” 172.

[41] Deuze, Media Life, 2.

[42] Kennedy, “Rhetorics of Sharing,” 129.

[43] John, The Age of Sharing; John, “Sharing and Web 2.0.”

[44] Facebook, “Facebook Redesigns Privacy.”

[45] John, The Age of Sharing, 5.

[46] Kennedy, “Rhetorics of Sharing,” 131.

[47] John, “Sharing and Web 2.0,” 167.

[48] Wittel, “Qualities of Sharing and Their Transformations in the Digital Age,” 6.

[49] Mirghani, “The War on Piracy,” 117.

[50] Kaminski, “Studying Norms and Social Change in a Digital Age,” 326; Vaidhyanathan, Copyrights and Copywrongs, 15.

[51] This article does not claim ‘sharing’ to be the opposite of copyright or ‘piracy’, nor that all internet searches for sharing are made in relation to queries about copyright; rather, this study investigates patterns of metaphor usage to provide insight into evolving public perceptions of these terms and strategies of the copyright discourse.

[52] Jun, “Ten Years of Research Change Using Google Trends,” 85.

[53] Stephens-Davidowitz, Everybody Lies, 4.

[54] https://trends.google.com. Google is the world’s primary search engine and performs 88% of global internet searches (over 3.5 billion searches each day) and 91% of Australian internet searches: Statista, “Search Engine Market Share Worldwide 2019”; Statista, “Google Market Share Countries 2019.”

Google search volume measures traffic for a specific keyword relative to all queries submitted in Google, normalised to a range from 0 to 100, with 100 corresponding to the peak of relative search volume obtained for each keyword during the period of interest.

[55] Baram-Tsabari, “What’s New?” 105.

[56] For example, to measure the impact of introduction of the US Copyright Alert System on internet searches for piracy (Leeuw, “Using Big Data to Study Digital Piracy and the Copyright Alert System”) and demonstrate public awareness of French anti-piracy laws (Danaher, “The Effect of Graduated Response Anti-Piracy Laws on Music Sales”).

[57] Ripberger, “Capturing Curiosity,” 253.

[58] Matsa, “Searching for News.”

[59] Reyes, “Using Internet Search Data,” 830.

[60] Whyte, “Thinking Inside the (Black) Box,” 1682. This means internet search data is a ‘valuable approach to understanding the cumulative activity—distinct from the eventual preferences—of members of target populations for social scientists’. That is, internet search data represents a measure of the public behaviour of mobilisation (rather than opinion) to seek out information about a topic in issue.

[61] Coyle, “‘To Buy or to Pirate’,” 1034; Dilmperi, “Toward a Framework,” 435; Kennedy, “Sharing in Networked Culture,” 8–36; Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax,” 211.

[62] Groves, “Three Eras of Survey Research,” 870; Leeuw, “Using Big Data to Study Digital Piracy and the Copyright Alert System,” ch 6.

[63] Tourangeau, “Sensitive Questions in Surveys,” 859.

[64] Coyle, “‘To Buy or to Pirate’,” 1036; Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax,” 208; Phau, “Pirating Pirates of the Caribbean,” 315.

[65] Anderson, “Political Ideology and Racial Preferences in Online Dating,” 28; Leeuw, “Using Big Data to Study Digital Piracy and the Copyright Alert System”; Tay Wee Teck, “Tracking Internet Interest in Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids Using Google Trends,” 52.

[66] Hardy, “Pre-Release Leaks.”

[67] Askitas, “The Internet as a Data Source for Advancement in Social Sciences,” 9.

[68] Askitas, “The Internet as a Data Source for Advancement in Social Sciences,” 3.

[69] Whyte, “Thinking Inside the (Black) Box,” 1682.

[70] Reyes, “Using Internet Search Data,” 830. The study used Google Trends to measure changes in economic and social attitudes in Chile. Over the period in question, Chilean society was known to have moved from a perspective of ‘economic development’ to ‘social responsibility’, and the researchers were able to demonstrate their methodology captured this shift in perceptions.

[71] Loughlan, “Pirates, Parasites, Reapers, Sowers, Fruits, Foxes,” 213. Loughlan uses this phrase to describe a group of words that leverage a similar set of rhetorical associations.

[72] Reyes, “Using Internet Search Data,” 836.

[73] MacNeill, “Torrenting Game of Thrones,” 546. Mirghani notes this ‘linguistic aggression’ is set against a background discourse on the ‘war on terror’ and ‘war on drugs’, using an ‘increasingly militarised language that relies on metaphors of war to inspire fear among audiences and to criminalise even the most casual of informational exchanges’: Mirghani, “The War on Piracy,” 114.

[74] John, The Age of Sharing, 20–43; Kennedy, “Sharing in Networked Culture,” 8–36.

[75] Kennedy, “Rhetorics of Sharing,” 135.

[76] Launched in 2006, Google Trends search data is available from 2004 to the present.

[77] For all Google Trends SQIs, the settings used were [location = Australia], [time-period = all available (2004 – present)], [all categories], and [web search]. Google Trends displays, for a given search term over the selected time frame, the relative monthly search volume (‘Query Index’) on a scale from 0 to 100 (maximum 100). It is important to note this number does not represent the absolute volume of searches on a topic, but a relativised and normalised proportion of all Google searches for that period.

[78] As Google Trends is an indicator of relative search interest, not absolute search volume, comparison of search terms against stable high-volume benchmark terms is appropriate. ‘Love’ and ‘life’ are neutral reference search terms that have been adopted as benchmark terms in a number of internet search-based studies as the ‘most widespread and popular keywords in the global web, “blogosphere” and web news’: Funk, “The Importance of Cultural Knowledge and Scale,” 3104; Nghiem, “Analysis of the Capacity of Google Trends”; Malcevschi, “Opportunities for Web-Based Indicators in Environmental Sciences.”

[79] Note that some peaks coincide with release of instalments in the Pirates of the Caribbean movies (July 2006, May 2007, May 2011 and May 2017) and can be disregarded for the purposes of this study.

[80] ALRC, Copyright and the Digital Economy, 87.

[81] Roadshow Films Pty Ltd v Telstra Corporation Ltd [2016] FCA 1503, FCA.

[82] Department of Infrastructure, “Copyright Modernisation Consultation.”

[83] Sensis, Sensis Social Media Report 2017, Chapter 1 - Australians and Social Media, 9.

[84] Sensis, Yellow Social Media Report 2020 - Consumers, 12.

[85] Department of Infrastructure, “2020 Consumer Copyright Infringement Survey”; Sensis, Yellow Social Media Report 2020 - Consumers.

[86] Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax”; Suzor, “Free-Riding, Cooperation, and Peaceful Revolutions in Copyright”; Department of Infrastructure, “2020 Consumer Copyright Infringement Survey”; MacNeill, “Torrenting Game of Thrones.”

[87] John, The Age of Sharing; Kennedy, “Rhetorics of Sharing.”

[88] Baram-Tsabari, “What’s New?”

[89] Note issues of uneven access to, and use of, the internet by different geographic and demographic populations raises issues of sample representativeness are unlikely to be significant to this study, due to the online context of the issue being studied. See Ripberger, “Capturing Curiosity,” 251.

[90] Mellon, “Internet Search Data and Issue Salience.”

[91] Generally, in the range of 1,000 to 10,000 average searches per month, which represents <0.0005% of the Australian population.

[92] It is important to note that issue salience is interested in the ‘Most Important Problem’ (MIP) in public opinion (Mellon, “Internet Search Data and Issue Salience,” 45), whereas internet search data is useful to investigate cumulative search activity (rather than preferences) for a topic by a population (Whyte, “Thinking Inside the (Black) Box,” 1682).

[93] Nuti, “The Use of Google Trends in Health Care Research.”

[94] Whyte, “Thinking Inside the (Black) Box,” 1690.

[95] Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax,” 233.

[96] Larsson, Conceptions in the Code, 7.

[97] Cohen, “Gore, Gibson, and Goldsmith,” 267; Larsson, “Conceptions in the Code,” 1025.

[98] Levi, “An Introduction to Legal Reasoning,” 506, 574.

[99] Lakoff, Metaphors We Live By, 23.

[100] Bosher, “An Analysis of the Fundamental Tensions between Copyright and Social Media.”

[101] Department of Infrastructure, “2020 Consumer Copyright Infringement Survey.”

[102] Suzor, “Free-Riding, Cooperation, and Peaceful Revolutions in Copyright,” 140; Dootson, “The Game of Clones and the Australia Tax,” 233, 234.

[103] John, The Age of Sharing; Kennedy, “Rhetorics of Sharing”; Phau, “Pirating Pirates of the Caribbean.”

[104] Larsson, Conceptions in the Code, 10.

[105] Levi, “An Introduction to Legal Reasoning,” 506.

[106] Kennedy, “Rhetorics of Sharing,” 131.

[107] Young, “A Hack for the Encouragement of Learning,” 44.

[108] Cohen, “Gore, Gibson, and Goldsmith,” 275; Loughlan, “Pirates, Parasites, Reapers, Sowers, Fruits, Foxes,” 214.

[109] Loughlan, “Pirates, Parasites, Reapers, Sowers, Fruits, Foxes,” 215.

AustLII:

Copyright Policy

|

Disclaimers

|

Privacy Policy

|

Feedback

URL: http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/LawTechHum/2021/19.html